Donald Duck pull toy was a 1940s hit

February 2022

Vintage Discoveries

Donald Duck pull toy was a 1940s hit

~ by Ken Weyand ~

As a youngster, one of my favorite comic-strip characters was Donald Duck, a creation of the Walt Disney Co. in the 1930s. Like many of his contemporaries, Donald was a purveyor of innocent fun, his pompous personality inviting the many situations he found himself in. Over the years, Disney added his family of nephews; his forever girlfriend, Daisy; and eventually his rich uncle, “Scrooge McDuck.”

I was one of millions of kids who helped fund the Disney empire, buying many Donald Duck comics at the Zumsteig drug store in Memphis, MO, our county seat. I was also in the crowd of youngsters at the Saturday matinee at the Time Theater, where westerns starring Roy Rogers, Gene Autry and Hopalong Cassidy were eagerly devoured, along with 10-cent popcorn. But we always cheered when the cartoons came on, and appreciated our weekly ration of Donald Duck, Bugs Bunny, and other favorites.

According to Wikipedia, Donald Duck has appeared in more films than any other Disney character, and was included in TV Guide’s list of the 50 greatest cartoon characters of all time in 2002. Outside the “action hero” genre, Donald is the most published comic book character in the world.

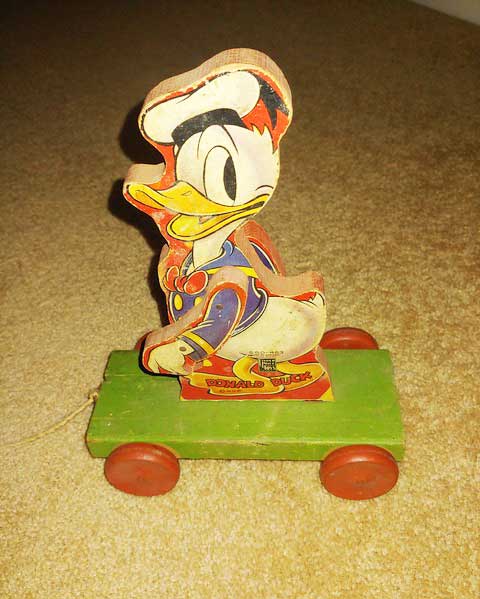

Early 1940s Donald Duck pull-toy

I’m keeping it

Similar Donald Duck pull-toys can be found on Ebay, with most prices ranging from $40 to $80. But mine’s not for sale. I’m keeping it as a reminder of my early days as a farm kid, when my heroes included Roy, Gene, Hopalong, and yes, Donald Duck.