~ December 2017 / Traveling with Ken ~

Vintage Discoveries

Only ghosts remain in Arkansas mining town

~ by Ken Weyand ~

Unlike the many pop-ulated hamlets that dot the Ozarks countryside, the old mining town of Rush is a true ghost town. Located 16 miles south of Yellville, AR near the banks of the Buffalo River, the remains of Rush are uniquely protected and documented in the Buffalo National River Historic District.

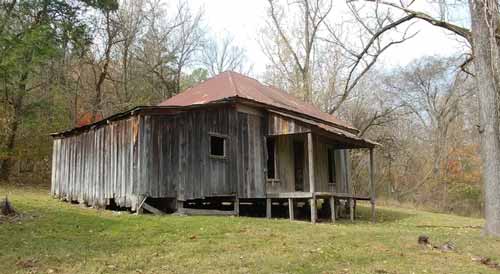

The remains of one of Rush’s mercantile buildings (present-day photos by Ken Weyand)

Rush (named for its proximity to Rush Creek, a tributary of the nearby Buffalo River) blossomed in the late 1800s as prospectors, searching for fabled Indian silver mines, instead found zinc. In 1886, thinking they had found silver-bearing ore, the prospectors built a smelter and started digging.

According to a 1911 account by Otto Ruhl in the Mining and Engineering Journal, “They built a rock furnace, charged it with charcoal, put in their ore, and started the blast. (But) from the opening in the bottom no silver came, but the prettiest rainbows imaginable floated over the stack of their blast.”

One of the residences still standing on the outskirts of Rush

Broke and discouraged, they reportedly tried to sell their claim to another prospector for a can of oysters, but he turned them down. Eventually the claim was sold to George Chase, whose Morning Star Mine became the first of 15 mines in the town.

In fact, the Morning Star is said to have been one of the largest producers of zinc in Arkansas. A miner extracted a single mass of pure Smithsonite, or zinc carbonate, that weighed nearly 13,000 pounds. The colossal nugget received blue ribbons at the 1893 Chicago Worlds Fair, and is currently on display at the Field Museum. Another large nugget was said to have won a blue ribbon at the 1904 St. Louis World Fair.

In addition to the white zinc oxide cream used today to ward off sunburn, zinc is used in many alloys, including brass. Early Romans and Greeks used zinc in brass-making and in health potions. The demand for zinc reached a peak during World War I, when munitions factories kept mines busy and their owners wealthy.

Old smelter, where the first miners discovered their search for silver yielded zinc

In Arkansas, the boom in zinc prices drew miners to Rush, swelling the town’s population to an estimated 5,000. As early as 1900, the town was bustling with three hotels, several restaurants and general stores, and other businesses. Houses couldn’t be built fast enough; eager miners and their families put up tents on the surrounding hills. Nearly everyone in a family could find work, including young boys who could be “water boys.” Pay averaged 19 to 35 cents an hour.

According to Bill Dwayne Blevins, writing in the Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture, Rush attracted a wide variety of prospectors, all hoping for quick riches. Merchants and land speculators followed. Not all of the newcomers were upstanding citizens. “A few prospectors coming to the area were striving to get as far from the law as possible,” Blevins wrote.

“In 1916, documents were filed incorporating Rush into a city,” Blevins stated. “Rush was recognized as the most prosperous city per capita in Arkansas.”

According to the Historic District, one of the first buildings built by the Morning Star Mining Company was a livery barn for the working horses and mules. Since roads were scarce and the Buffalo River was too shallow for barges, teamsters would haul the ore in wagons over rough trails east to Buffalo City. From there it was barged on the White River to railheads. On the return trip they would bring back supplies for Rush residents. By the early 1900s, railroads reached Yellville and Buffalo City, making shipments easier.

Miners in early 1900s rest in their tent in the hills above Rush. (National Park Service)

A ghost town is born

When the Great War ended Nov. 11, 1918, the price of zinc collapsed, and Rush quickly declined. One after another, the mines closed. According to the National Park Service, a mining revival was attempted in the 1920s but was unsuccessful. A few residents stayed on into the mid-1950s, some of them making a meager living by “free-ore-ing” abandoned mines. But the Post Office closed, and the remaining settlers gradually left, making Rush a true ghost town. In 1972, Rush became part of the Buffalo River National River Heritage District. In 1987, the District was placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Today visitors can see the remains of residential buildings, a mercantile building and a few foundations as they drive through the district. Boaters can access the Buffalo River, located a few hundred yards beyond the old town.

Morning Star Hotel in its later years (National Park Service)

For those who pause to explore the ghost town, information markers show history, maps, and old photos. Although several mining districts once flourished in northern Arkansas, Rush is the only one that still has ruins, buildings, mine tailings and other structures to give visitors an idea how it would have appeared in its heyday.

In the 1980s, the mines were deemed unsafe with crumbling ceilings. Fences and gates were erected, and visitors are not permitted in the mines. However the gates were specially designed to allow a large bat population to come and go freely.

Much of Rush can be seen by road, and parking is available. Trails allow visitors to see more of the Heritage District, including the mines, although entering the ruined buildings and mines is prohibited.

The Rush Heritage District is located 16 miles south of Yellville, AR. Take AR 14 about 12 miles and turn left onto 6035. For more details call the National Park Service (Buffalo National River) at 870-365-2700, or download their brochure at Rushletter.pdf.

Ken Weyand can be contacted at kweyand1@kc.rr.com Ken is self-publishing a series of non-fiction E-books. Go to www.smashwords.com and enter Ken Weyand in the search box.