Valentine boxes evoke childhood memories

February 2024

SMACK DAB IN THE MIDDLE

Valentine boxes evoke childhood memories

by Donald-Brian Johnson

Here’s a memory-jogger: it’s Valentine’s Day in mid-20th century America, and across the country, nearly every elementary school classroom has something in common. Atop each weatherbeaten desk sits a “valentine box.” It began life as just another old shoebox, but now, carefully covered in colorful construction paper, and festooned with cutout red hearts, it’s been transformed (For the less artistically inclined, there were “valentine bags”—grocery sacks, minus the construction paper, but still sporting an array of drawn or pasted hearts).

Each receptacle had an opening cut into it, ready to receive its quota of cards — and there was a quota. Everybody gave a valentine, and everybody got one. That included the tough kid across the aisle who, every so often, “borrowed” your lunch money—and that girl with the braids, who accidentally mushed your favorite Crayola.

Lessons over, the teacher finally announced, “you may look at your valentines.” Box covers came off, bag tops were unrolled, and each student eagerly perused his or her “take” (after carefully counting them first). There were generic “to a friend” valentines, with illustrations of romping cats or puppies.

There were funny valentines, with chortle-provoking corny puns. There may even have been a valentine with an innocent romantic message — one that had you looking at that girl with the braids through different eyes.

Then, the school bell rang. Your valentines were packed up, brought home, and piled in a box of “school papers,” alongside their compatriots from previous years. Out of sight, and out of mind. Remember?

According to legend, the first valentine greeting was sent by the man himself: St. Valentine (Actually, there are at least three “St. Valentines,” each clamoring to be recognized as the day’s patron saint, but here’s the most romantic story).

A third-century clergyman, this Valentine was imprisoned for performing marriages in defiance of Emperor Claudius II, who’d decreed that all men of military age must remain single. While in prison, Valentine fell in love with his jailer’s daughter, declaring his feelings in a note signed “from your Valentine.” Since Valentine was eventually beheaded, the story lacks a happy ending, but nonetheless, a tradition was born.

The oldest-known written valentine dates from 1415, a poem the Duke of Orleans sent to his wife while imprisoned in the Tower of London. Shortly thereafter, King Henry V began sending valentines to his favorite, Catherine of Valois, although Henry hired a professional poet to do the heavy lifting.

By the 1700s, kings and dukes weren’t the only ones dispensing valentines. Each Feb. 14th, handwritten valentine messages made their way across all levels of society, often accompanied by small gifts. The dawn of mass printing and inexpensive postal rates meant that, by the early 1800s, just about anyone who wanted to could send, (and hopefully, receive), a valentine.

In the 1840s, ready-made valentines swept the United States, thanks to Esther A. Howland (now hailed by grateful retailers as the “Mother of the Valentine”). Her creations were quite lavish, incorporating ribbon, lace, and colorful bits of material. Joining the traditional visuals of hearts and flowers was “Cupid,” that little winged fellow with the bow and arrow. It was a logical choice: in ancient Roman mythology, Cupid’s the son of Venus, goddess of love.

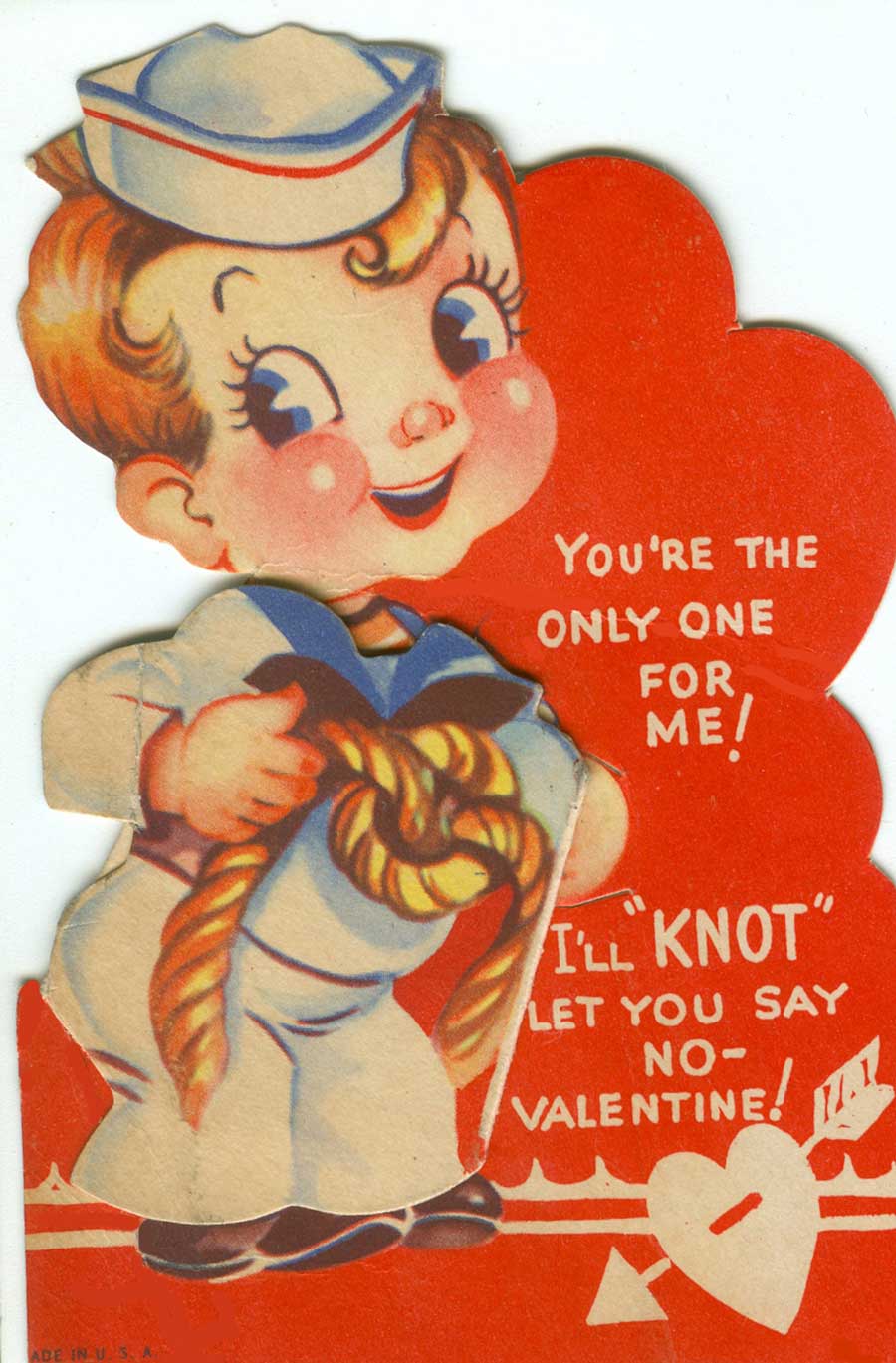

Vintage Valentine card

A Nautical-themed single-sheet Valentine from the 1940s. Image courtesy of the author and photography associate Hank Kuhlmann.

Nowadays, the Greeting Card Association notes that more than one billion valentines are sent annually, vs. two-and-a-half billion Christmas cards. Women buy 85 percent of them (which should have plenty of husbands and boyfriends hanging their heads in shame).

Valentines (including the ones you saved from grade school), remain popular with collectors, who enjoy their colorful visuals, whimsical themes, varied functions (for instance, pop-up, or moving-part valentines), and affordable prices (most are under $5). Displayed singly, or framed in a montage, vintage valentines add a touch of nostalgia to any décor. They’re also guaranteed to rekindle plenty of nostalgic memories—of carefree days, childhood friends. . .and, of course, the “valentine box.”

Donald-Brian Johnson is the co-author of numerous Schiffer books on design and collectibles, including “Postwar Pop,” a collection of his columns. Please address inquiries to: donaldbrian@msn.com