Built in the late 1820s, the three-room log cabin where American outlaw Jesse James was born was owned by the family from 1845 until the late 1970s, when it was sold to Clay County, MO. (photo courtesy of Elizabeth Gilliam Beckett)

Historic Site in Missouri

One historic site in Missouri stands as a testament to the lawlessness of the American frontier of the 19th century, with thousands of visitors from all over the world visiting it each year to learn about the life of the great outlaw Jesse James.

According to Elizabeth Gilliam Beckett, historic sites manager for Clay County, MO, which includes the Jesse James Farm and Museum in Kearney, an estimated 10,000 to 12,000 make the trip to the site every year. There, she says, they learn to separate the myth of Jesse James from the facts about his infamous deeds.

“The biggest misconception about Jesse James is that he was a ‘Robin Hood,’” Beckett says of the legendary character who stole from the rich and gave to the poor.

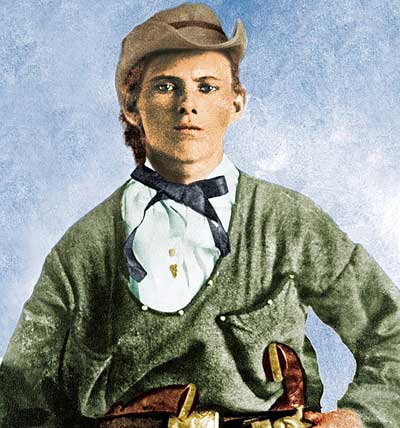

The young Jesse James, shown here in a colorized photo at age 14, adopted his family’s staunch pro-Confederate and pro-slavery views. (image courtesy of PBS.org)

The young Jesse James, shown here in a colorized photo at age 14, adopted his family’s staunch pro-Confederate and pro-slavery views. (image courtesy of PBS.org)

Forged by hate and bloodshed

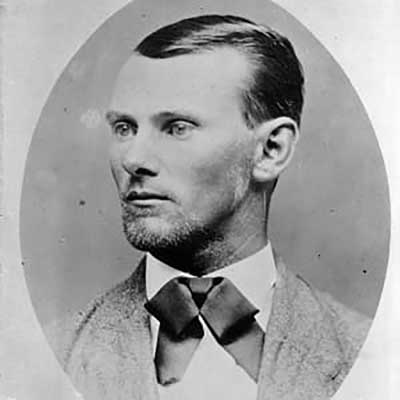

The real Jesse James was much more complicated and much less worthy of adoration. Born Jesse Woodson James on Sept. 5, 1847, near Kearney, he grew up in the “Little Dixie” area of Missouri, a wide swath of 13 counties heavily populated by Southerners who emigrated there, bringing their cultural and political practices – including slavery. Little Dixie includes the region between the Mississippi River north of St. Louis to Missouri counties in the central part of the state.

As the Civil War brewed, the teenaged James grew up in a household with decidedly pro-Confederate views. He and his brother, Frank, even joined pro-Confederate guerillas, pledging their allegiance to William Quantrill and “Bloody Bill” Anderson, two guerilla leaders who traversed Missouri and Kansas in a violent hunt for escaped slaves. The James brothers, especially Jesse, terrorized the guerillas’ enemies.

“He helped to tear apart his community without reflection or self-doubt,” historian T.J. Stiles wrote in his biography, “Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War,” published in 2002. “Seized by his hatred and ideological convictions, he could not see himself for what he was. Instead, he reveled in the powers his murders earned him.”

After the nation’s bloodiest war had come to an end, having already acquired a taste for looting during the 1864 Centralia Massacre, in which Confederate forces captured and executed two dozen Union soldiers in Centralia, MO, Jesse and Frank James joined the ranks of other former Confederate guerillas in living the lives of outlaws. The men robbed trains, banks, and stagecoaches throughout the Midwest, becoming household names nearly overnight, amassing other disillusioned men to join their gang for the decade following the war.

‘A common thug’

Still, Stiles writes, the media of James’ day – and James himself — portrayed him as a modern-day Robin Hood, despite the fact that no evidence existed of James sharing the money he stole with those less fortunate.

“Jesse James was not an inarticulate avenger for the poor,” Styles writes in his biography of James. “His popularity was driven by politics – politics based on wartime allegiances – and was rooted among former Confederates. … He promoted himself as a Robin Hood; his enemies derided him as a common thug.”

Jesse James was finally done in by a member of his own gang – Robert Ford, a new recruit whose act of murder was fueled by the promise of a bounty on James and by the promise of amnesty for the crimes he had committed. Ford shot James in the back of the head on April 3, 1882. Though he wasn’t paid the entire $10,000 bounty, Ford was granted a full pardon by Missouri’s governor and lived out the rest of his days posing for photos in dime museums as “the man who killed Jesse James.” He also re-enacted James’ murder in a touring stage show. Ford took his own life on May 4, 1884.

Zerelda James, Jesse’s mother, stands at his gravesite in 1882. During an 1875 raid on her house by the Pinkertons, who were looking for Jesse, authorities tossed an explosive device into the house that detonated and mangled Zerelda’s arm so badly that it had to be amputated below the elbow. After Jesse’s death, Zerelda gave tours of the cabin in which Jesse was born, and for just 25 cents, visitors could take home a souvenir pebble from Jesse’s headstone. (Image courtesy of PBS.org)

Kearney’s Jesse James Festival has taken place every September for 50 years. (photo courtesy of KCParent.com)

In Kearney and nearby St. Joseph, MO, where the house in which James was killed still stands as another historic site of interest, signs of Jesse James’ influence are everywhere – the Jesse James Antique Mall and Furniture Gallery, right off Interstate 29 in St. Joseph, has drawn bargain hunters for decades. And in Kearney, the annual Jesse James Festival – a family-friendly event – has brought crowds to town for 50 years.

“The reality is that Kearney hosts a festival that brings a large collection of people from all walks of life together,” according to the festival’s website. “They gather, not to pay tribute to an outlaw, but to be reminded of an historical era which had a great impact on our country.”

Passing on into infamy

Jesse James, of course, lived on in the decades afterward, not only in word-of-mouth stories of his robberies and other infamous deeds, but in numerous media forms, including music, literature, and Western films.

“In the end, (James) emerges as neither epic hero nor petty bully, but something far more complex,” historian T.J. Stiles writes. “In the life of Jesse James, we see a place where politics meets the gun.”

Obviously, Clay County’s Beckett notes, the festival helps offer a boost in the number of visitors each year.

“The Jesse James Festival is hosted by the city of Kearney, and the museum benefits from many visitors during that weekend,” she says.

The 2021 Jesse James Festival will take place Sept. 10-11 and Sept. 16-19 at Jesse James Park in Kearney.

Life on the family farm

Still, the museum is a must-visit site when it comes to learning not just about Jesse James the man and legend, but also the tumultuous times in which he lived. The members of the James family were not the first to live on the farm – that distinction, according to historian Phil Stewart, goes to a pair of twin brothers, Jacob and David Groomer, who purchased a tract of land near Kearney in 1822 and built a farm upon it. The brothers built a three-room log cabin on the farm, too, and various members of the Groomer family lived in it for the next 20 years.

A young Baptist preacher, Robert James, and his wife moved to town and bought “the old Groomer place” in October 1845 for $1,640. Most of his children, Jesse included, were born in the log cabin.

Stewart continues, “It was here that Jesse James swore vengeance against the Union, and it was here that he carried on his personal war against society. Robberies were planned here. Posses and detectives lurked in the trees north of the house. And it was here that history was made. The old house has seen more than its share of tragedy and sorrow.”

The government of Clay County, MO, has owned and operated the James farm since 1978. Photo courtesy of TheWalkingTourists.com

“No place on God’s green earth has closer ties to Jesse James than does the James Farm and the house that is still its centerpiece,” Stewart wrote in an historical article about the farm. “He was born here, and it remained a safe haven and place of comfort throughout his life. His body would be brought here after his death in 1882, and it was here that he was laid to rest in the corner of the yard where he had played as a boy.”

Jesse James’ body was originally buried on the family farm but later moved to the Mount Olivet Cemetery in Kearney. The original footstone remains on the farm. (photo courtesy of Elizabeth Gilliam Beckett)

Ownership of the farm changed hands between descendants of Jesse James for the next century, until 1978, when the Clay County government bought it from the James grandchildren and immediately began restoration work. The farm opened to the public the following year, when its board of directors founded the “Friends of the James Farm,” an organization of supporters designed to fund the continued maintenance and upkeep of the site through regular donations.

“The old place looks pretty much as it did more than 100 years ago,” historian Phil Stewart says of the property. “…The visitor can easily lose themselves in the history of the time and place.”

For her part, Beckett says the historic site doesn’t exist to glorify Jesse James, but to educate visitors about his life and the era that shaped his world view.

“The museum tells the story of a time period in history,” she says, “and the visitor can decide how they see him.”