The Maine Event – Quilting adventures with the American Quilt Study Group

February 2026

Covering Quilts

The MAINE Event – Quilty adventures with the American Quilt Study, Part 2

by Sandra Starley

A highlight of every year for lovers of quilt history (old and new) is meeting to share research, treasures, and friendship at the Annual Meeting/Fall Seminar of the American Quilt Study Group (AQSG). Last month, I shared some of the wonderful experiences I had visiting 2025’s meeting held in the coastal beauty of Portland, ME, with tours of the area and a visit to Wiscasset: “Maine’s prettiest village.” It was an amazing event full of old and new friends and a lot of antique quilts. In the previous article, I focused on the off-site tours, but there are many terrific events at the host hotel included with seminar registration. They included Early Maine Signature Quilts, a Special North Carolina Pattern, another Southern Design, an AQSG Icon, to Environmental Messaging Quilts of the21st Century.

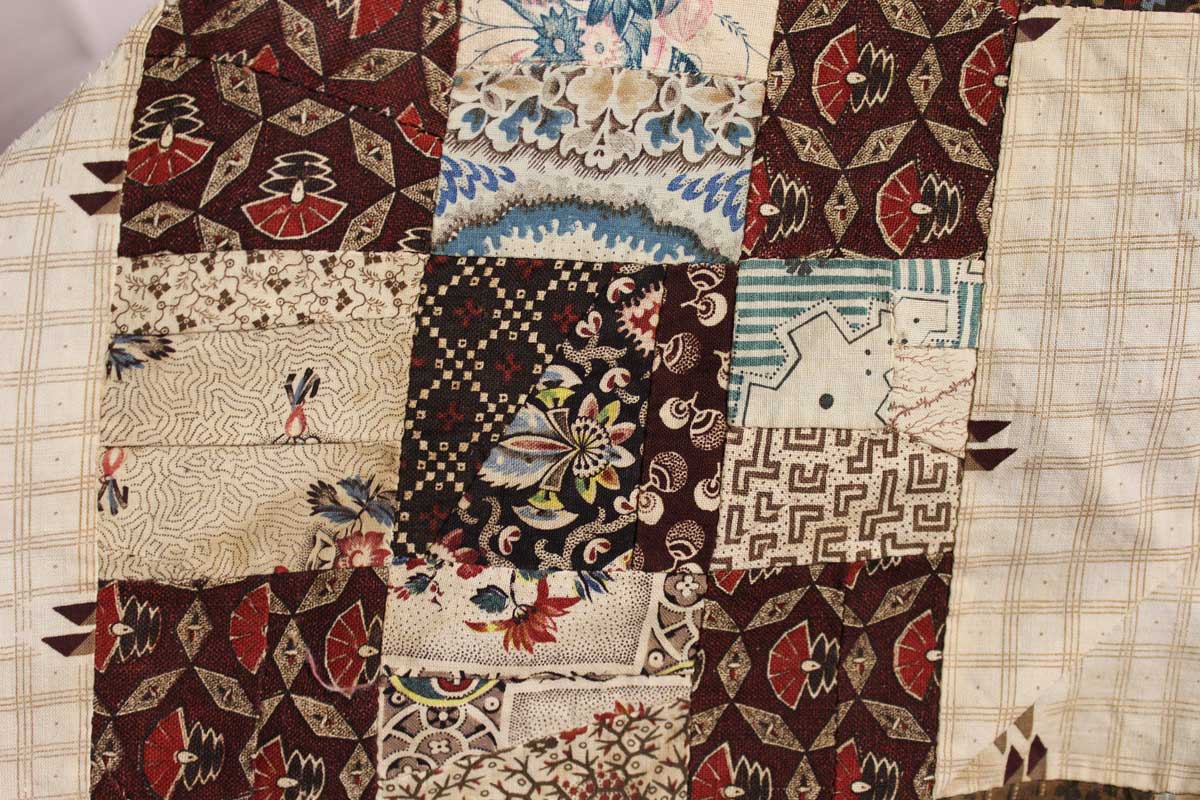

One of the highlights of every year’s seminar are the scholarly paper presentations. These are peer-reviewed research papers showcasing “the most recent advances in quilt-related research.” They are presented at seminar and published in Uncoverings, AQSG’s annual academic journal. These papers represent years of intense research by the authors who must condense that information into their paper and then further distill the material to a brief power point talk at seminar. As usual, we were treated to a stellar group of talks on a variety of quilt history, both past and present as indicated above. It was a delight to learn details about such a wide range of topics and time periods, from mid- to late 1800s signature quilts made in Cumberland County, ME, where the seminar was held.

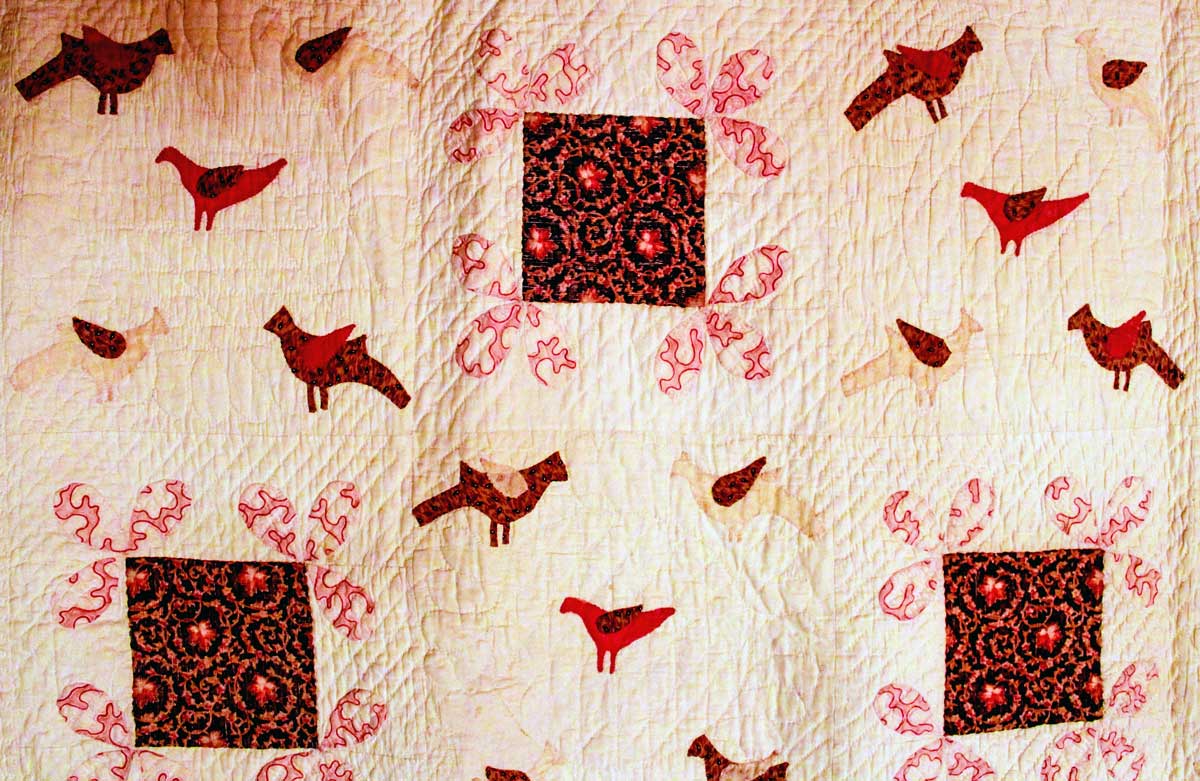

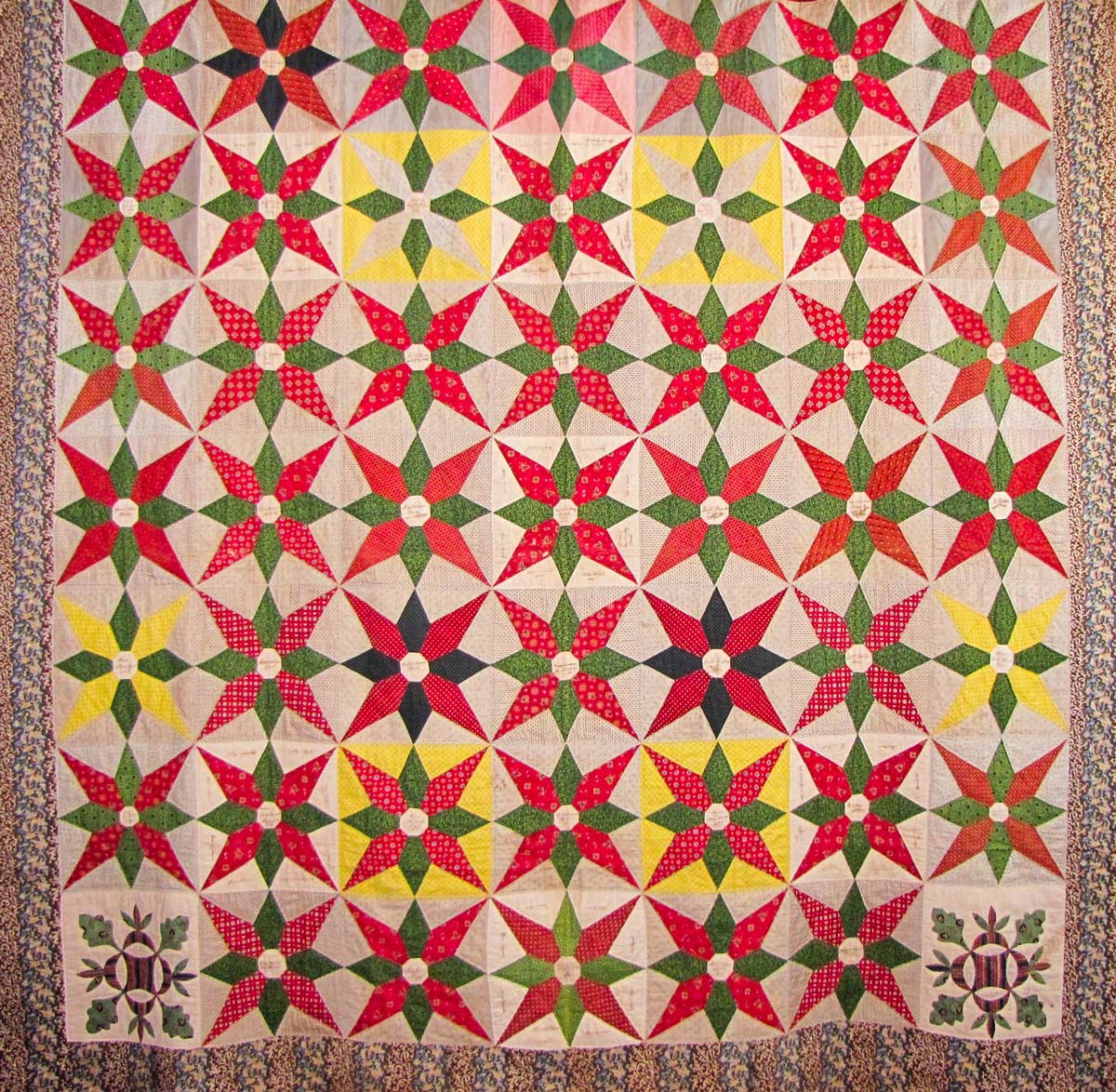

And on to the unique floral appliques on golden yellow backgrounds that hail from Alamance, NC. We learned more about another wonderful Southern pattern, the Harlequin Star. It was also interesting to hear about one of our founding members, Lucy Hilty, and her quilting life.

And lest you think quilt history is only about antique quilts, we saw the “transformational power” of environmental quilts being made today. So much to digest. Luckily, we all took home a copy of Uncoverings with the research papers.

Great food and Entertainment

Seminar also features great food paired with informative luncheon and dinner speakers. This year we enjoyed a keynote speech by independent scholar Lynne Basset on “Embedded: Quilts as Messengers.” Fellow appraiser Pam Weeks shared the “Long and Winding Road” of her life’s journey to quilting with a lot of skiing along the way. There was a special presentation by Elaine Yau, A’donna Richardson, and Julie Silber speaking on Routed West: Twentieth Century African-American Quilts in California and how the Berkeley Art Museum acquired a seminal collection (check out the amazing book Routed West).

Speaking of entertainment, yours truly along with my fellow Juliettes donned nautical costumes (Sandy Starfish, Kathy Cray-fish, Lenna De Marlin, etc.) in honor of Maine as part of the Live Auction along with the auctioneering pirate duo (Dana Balsamo and Julie Silber).

We, the high-kicking sea people, assisted in the auction along with engaging the crowd. Our outrageous outfits and dancing made for a lively evening and helped raise serious funding for AQSG thanks to our generous members. But the highlight was the sea shanty band headlined by our own sea shantress, Mea Clift. There were wonderful antique and contemporary quilts up for auction, along with treasures from beloved Maine quilter Judy Roche.

Tune in next month to learn about the study centers, the silent auction, the vendors mall, and more.

Paper presenter Laurie LaBar with a Cumberland County, ME, Album Quilt (1850) in her exhibit at the Maine State Museum (Image courtesy of the author)

Sandra Starley is nationally certified quilt appraiser, quilt historian, and avid antique quilt collector. She travels throughout the U.S. presenting talks on antique quilt history, fabric dating classes and trunk shows as well as quilting classes. Learn more at utahquiltappraiser.blogspot.com. Send your comments and quilt questions to SandraStarley@outlook.com