Food for thought: Feed sack art

June 2025

SMACK DAB IN THE MIDDLE

Food for thought: Feed sack art

by Donald-Brian Johnson

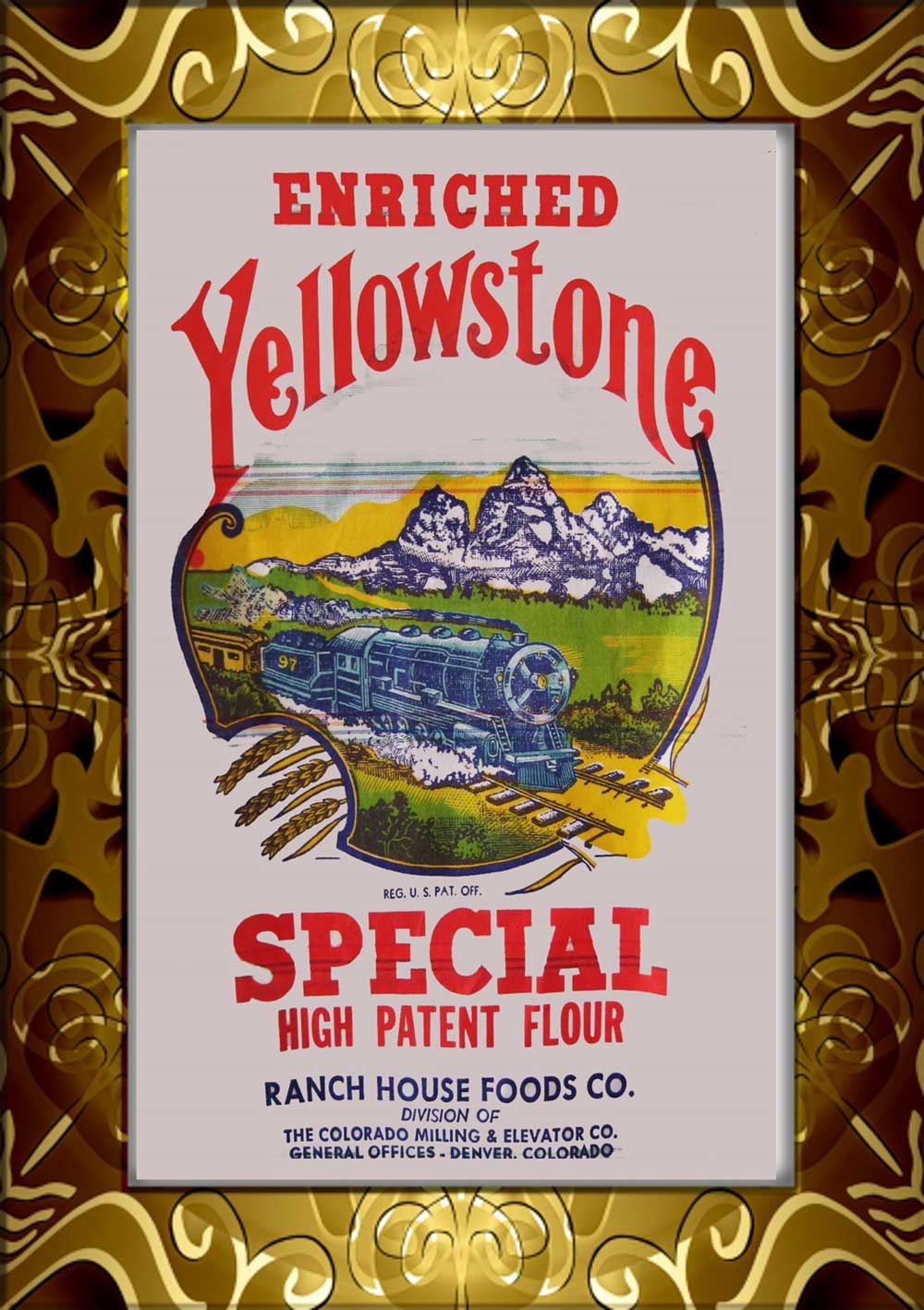

Beaming bakers. Knights in armor. Singing chickens, a solemn Sphinx, and even a corn cob or two, outfitted with airplane wings.

What gives? Well, one and all are examples of “feed sack art.” Those colorful logos on cotton feed sacks provided a healthy dose of Americana from just before the turn of the 20th century well into the 1950s.

Cloth feed sacks were the mid-1800s successors to the wooden barrels that had previously handled storage chores. Industrial sewing machines now made it possible to sew reliable seams. Although dubbed “feed sacks,” the bags were put to work carrying plenty besides animal feed. Among the contents: seeds, flour, sugar, tobacco, bath salts, corn meal, and even ammunition. While early bags were often burlap or jute, by the 1890s cotton was king. Cotton bags were more pliable, cheaper to produce, and reusable.

Actually, “repurpose-able” is a better description. No homemaker intended to refill her empty Blue Feather Potatoes bag with more potatoes. But with a good washing, and by picking out those sturdy seams, there were plenty of other uses for that good cotton–and there was plenty to use. The standard 100-lb. feed sack, when laid flat, measured approximately 37” by 43”. With enough bags, there was soon more than enough material on hand to sew up a variety of household necessities, from dish towels and bedsheets, to new curtains and quilt backings.

Just about the only thing early white cotton bags were less than desirable for: clothing. Initially, the logos and product information inked on the bags was there to stay. The only hope for removal: dousing them with bleach, or other “sure-fire” home remedies, before engaging in some vigorous scrubbing. If that didn’t do the trick, printed info was sometimes left as is. After all, who would see it? Only the disgruntled little girl heading off to school, knowing that her new set of drawers had “100 lbs. net weight” plastered across the posterior. (Patterned feed bags, which came into vogue for clothing use in the 1920s, solved the problem. Their labels and logos were either water-soluble ink, or on easily removable tags. This led to a surge in dresses, play clothes, aprons, and other types of feed sack clothing during the Depression and World War II years).

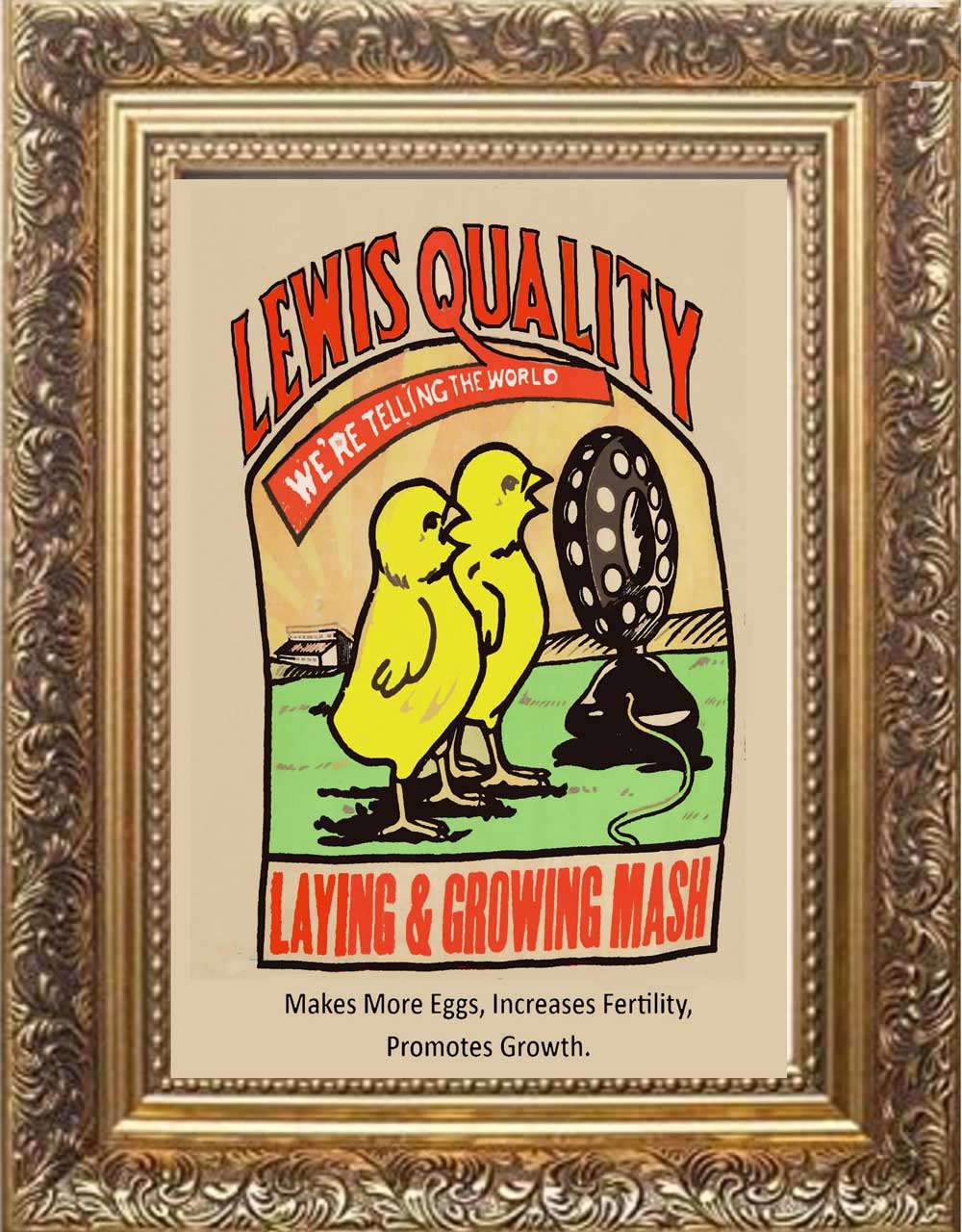

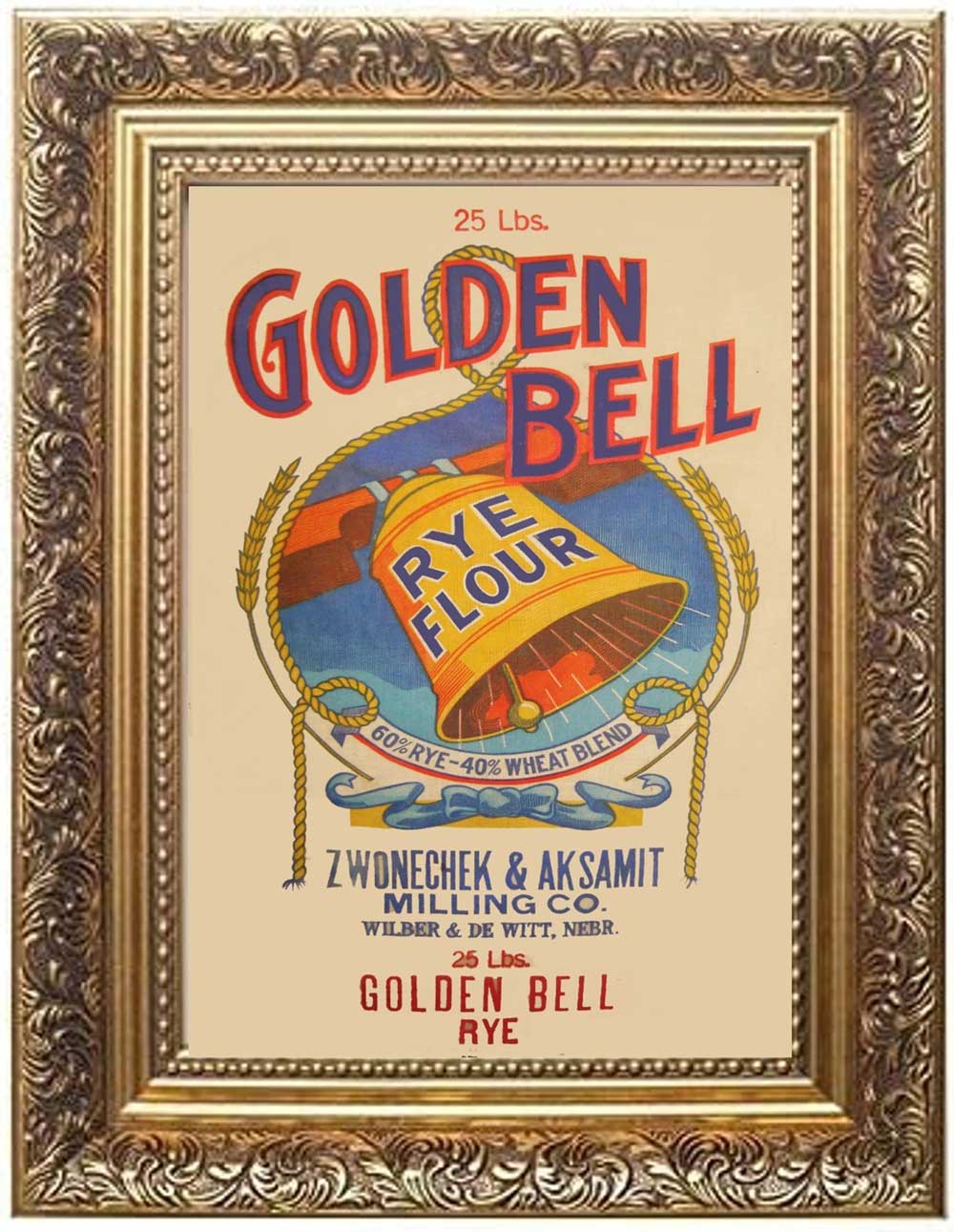

By the early 1940s, more than 30 companies were churning out feed sacks nationwide. There was an ongoing effort to come up with distinctive, uniquely-themed logos, sure to drum up buyer interest. This explains the warbling poultry and flying corncobs on some bags, which vied for attention with more traditional illustrations of farms and countrysides.

And they’re on the air! Chicken duo sings the praises of “Lewis Quality Laying and Growing Mash,” Lincoln, NE. (Image courtesy of Shari Aken and Hank Kuhlmann)

Ring out the news: “Golden Bell Rye Flour,” Zwonechek & Aksamit Milling Co., Wilber & DeWitt, NE. (Image courtesy of Shari Aken and Hank Kuhlmann)

For today’s collectors, accumulating feed sacks requires pre-planning. As noted, they’re huge. Unless you have plenty of room to hang them (say, in an empty barn), much of your collection could remain unseen. But if it’s just the feed sack logo you’re interested in, an attractive and workable alternative is to frame and display just the logo portion. As for the remainder of the bag, there’s no need to try stuffing it into the frame or cutting it up to get at the logo (As feed sack prices can range from $10-$50, depending on condition, put away those scissors!). The answer to the dilemma is as close as your camera or phone. Just photograph the logos, then print them for display. This allows for size adjustment of the image to fit the frame. It also offers the option of touching up any undesired deterioration. The result: an eye-catching display, true to the source, but with the original feed sacks remaining intact.

With the introduction of equally sturdy, yet much less expensive paper and burlap bags in the 1950s, the use of cotton feed sacks declined. Their logos, however, continue to hold a nostalgic appeal for today’s collectors. They hearken back to a simpler, more peaceful time. A time when chickens could sing, and corncobs could fly.