(Image courtesy of Classic Media)

Mar 2023

Cover Story

Walk Like An Egyptian

Egyptomania Resurrects Country’s Magic, Mysticism

by Corbin Crable

Though fascination with all things Egyptian has endured since the ancient world, it wasn’t until the last 200 years or so that the craze we know as “Egyptomania” really took off.

According to Kent Weeks, an American Egyptologist, Egyptomania can best be described as two things.

“First, it’s the interest in ancient Egypt in popular culture—National Geographic television specials, films like ‘The Mummy’ —things that appeal to the ordinary person on the street,” Weeks says in an article published by the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

“Second is the enthusiasm with which modern people take bits and pieces of ancient Egyptian culture and insert them into contemporary culture in things like architecture, design, or objects.”

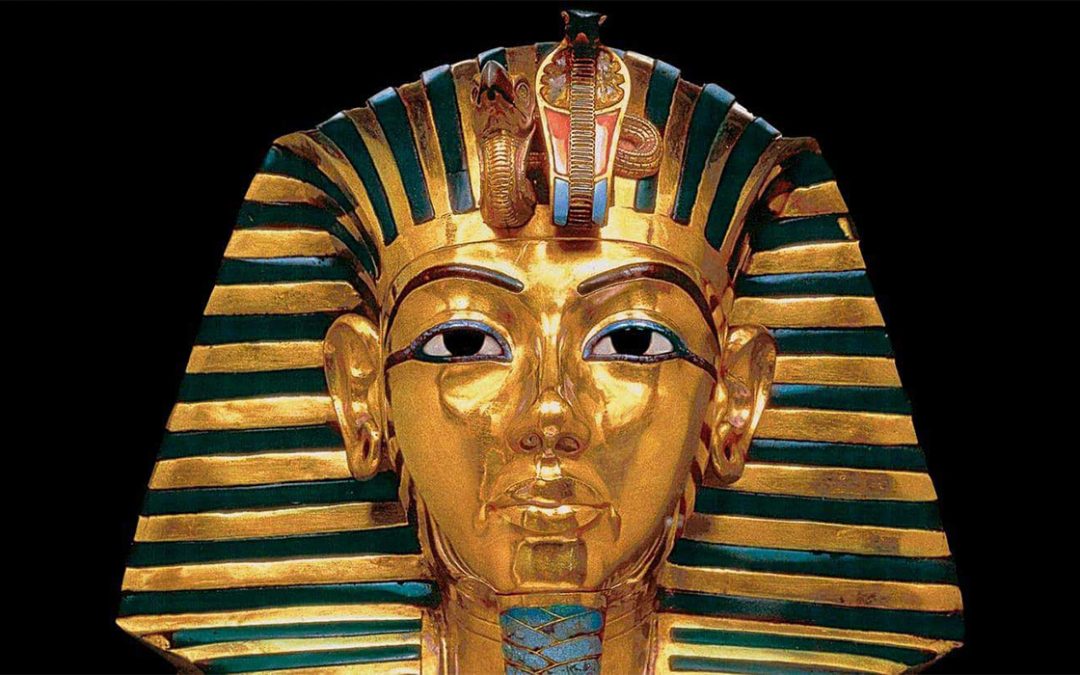

Long-lost jewelry from King Tut

Long-lost jewelry from King Tut’s tomb rediscovered a century later. (image courtesy of aeluc.dynu.net)

Late 18th century

In the late 18th century, interest in Egypt was revived when French General Napoleon Bonaparte invaded the country.

Bonaparte commissioned a team of nearly 200 scientists and scholars to study the art and culture of the country. One of the team’s most significant findings was the coveted Rosetta Stone, which unlocked the mysteries of Egyptian hieroglyphics to future generations of historians and anthropologists.

In the century following, the Victorian era became inexorably linked with Egyptomania. In fact, throughout the late 19th century, wealthy Victorians didn’t need museum artifacts to entertain themselves – the richest ones traveled to Egypt themselves and excavated tombs, robbing them of both riches and bodies. These Victorians would even host parties at which mummies would be unwrapped for entertainment.

Unearthing the Boy King

But the most recent resurgence of Egyptomania came in the early 20th century when archaeologists accompanied wealthy patrons to Egypt, where they excavated tombs in the hopes of unearthing treasures they could not only donate to museums but also add to their own personal collections.

The most important tomb excavation in modern history occurred in 1922 when archaeologist Howard Carter discovered the tomb of ancient Egypt’s King Tutankhamun, which Getty calls a “universally celebrated symbol of ancient Egypt,” featuring “a trove of funerary objects—furniture, jewelry, clothing, and elaborate wall paintings among them—(which) captured the popular imagination in unprecedented ways.”

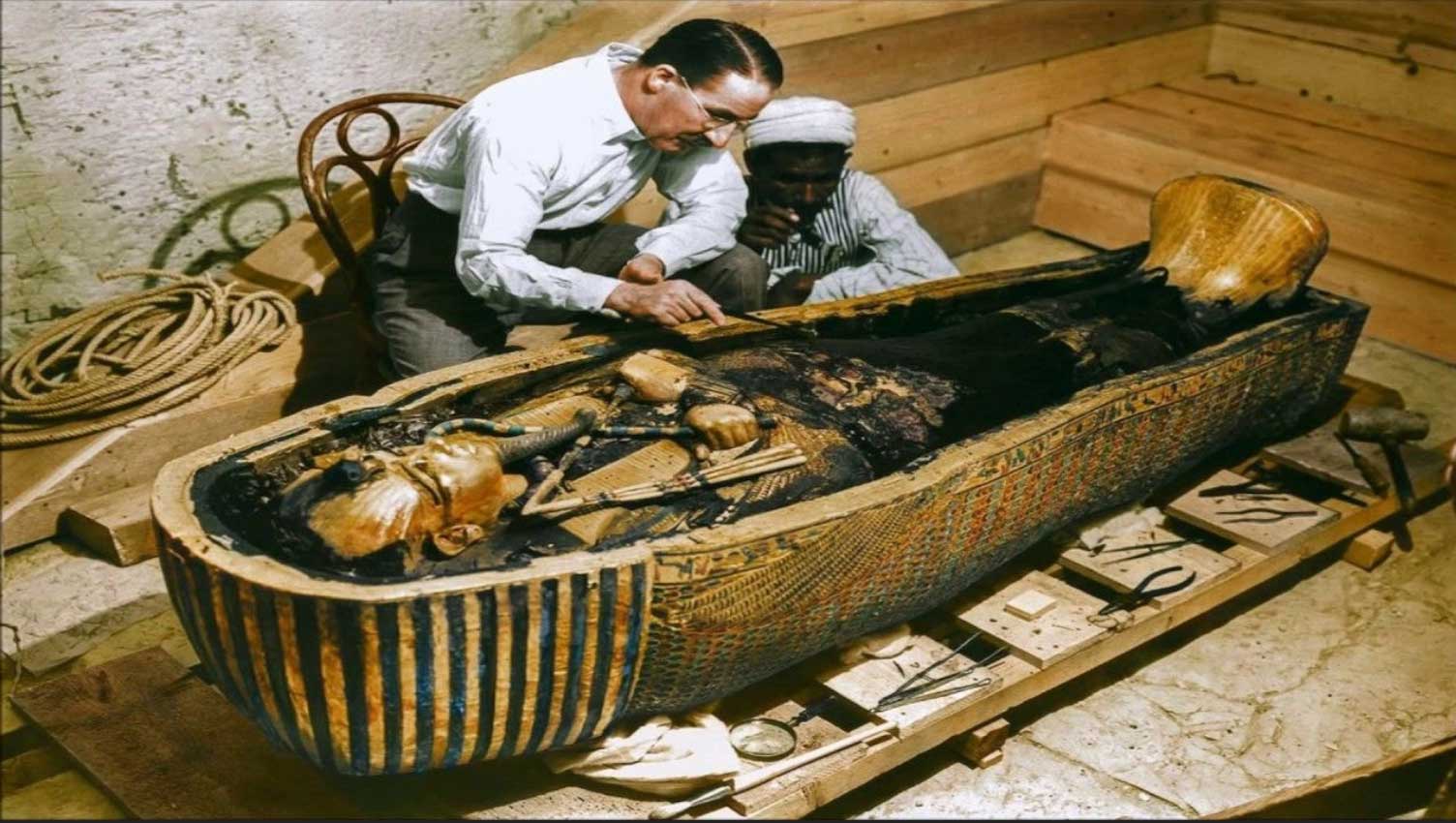

Mummy of King Tutankhamun.

Archaeologist Howard Carter studies the mummy of King Tutankhamun.

Carter discovered King Tut’s tomb in February 1922. (Image courtesy of

History.com)

Often called “the Boy King,” Tutankhamun rose to power as a child at age nine, with his reign lasting a decade (1333 B.C.-1323 B.C.); the circumstances surrounding his death remain a mystery, with theories tossed about that include murder, disease, and an unfortunate accident involving being thrown from his chariot and subsequently run over.

Carter’s discovery in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings was vast – works of art, statues, jewelry, clothing, a chariot, golden shrines, weapons, and, laying within an elaborately decorated sarcophagus, the mummified body of King Tut himself.

“The public devoured every crumb of information as King Tut’s tomb was painstakingly explored by British Egyptologist Howard Carter and his colleagues. The media was eager to fill the desire for information,” according to the Washington State Department of Archaeology. “Motion picture newsreels, magazines, and newspapers all featured the latest developments of the excavation. Two years after the discovery, in 1924, the New York Times Pictorial Magazine carried the first color photos shown in the United States of the treasures from Tut’s tomb. Articles about Tutankhamun carried well into the 1930s as archaeologists took 10 years to completely clear the tomb.”

With Carter’s discovery, an American obsession with all things Egyptian had begun, finding its way into architecture, fashion, art, and beyond.

Evening Gown

This evening gown, made by Callot Soeurs in 1925, was produced at the height of 1920s Egyptomania. Image courtesy of The Goldstein Museum of Design

Fashion

Examples of Egyptomania in textiles can be readily found, with the most stunning examples on display in museums worldwide.

“The designs, colors, and materials of unearthed Egyptian antiquities significantly impacted art and design for decades, especially via the 1920s and 1930s design movement now called ‘Art Deco,’” according to the Goldstein Museum of Design in St. Paul, MN. “Egyptian design elements thus found expression in architecture, interiors, graphic design, textiles, and fashion.”

A green silk dress in the museum’s collection was made by the Paris couture design house Callout Soeurs in 1925. A “masterful merger of design elements borrowed from ancient Egypt with 1920s fashion,” the dress features beading at the neck, center front, hipline, and hem, all off-white with a green border of beading around the bottom, according to the museum’s website. The color of the dress is especially interesting, since author Isabella Campagnol, in her 2022 book “Style From the Nile: Egyptomania in Fashion from the 19th Century to Today,” notes that in the earlier days of Egyptomania, “fabric colors named after Egypt were introduced in shades of green, blue-green, and umber.” Indeed, the beading and necklines of the flapper dresses of the 1920s found their inspiration from Ancient Egypt.

Campagnol also observes that accessories, too, of the 1920s were heavily influenced by Egyptian culture, with sphinxes, gods, heads of pharaohs, scarabs, and hieroglyphs featured heavily. Late last year, auction house Sotheby’s put on display a selection of valuable antique Egyptian-themed jewelry to mark the 100th anniversary of Carter’s discovery of King Tut’s tomb.

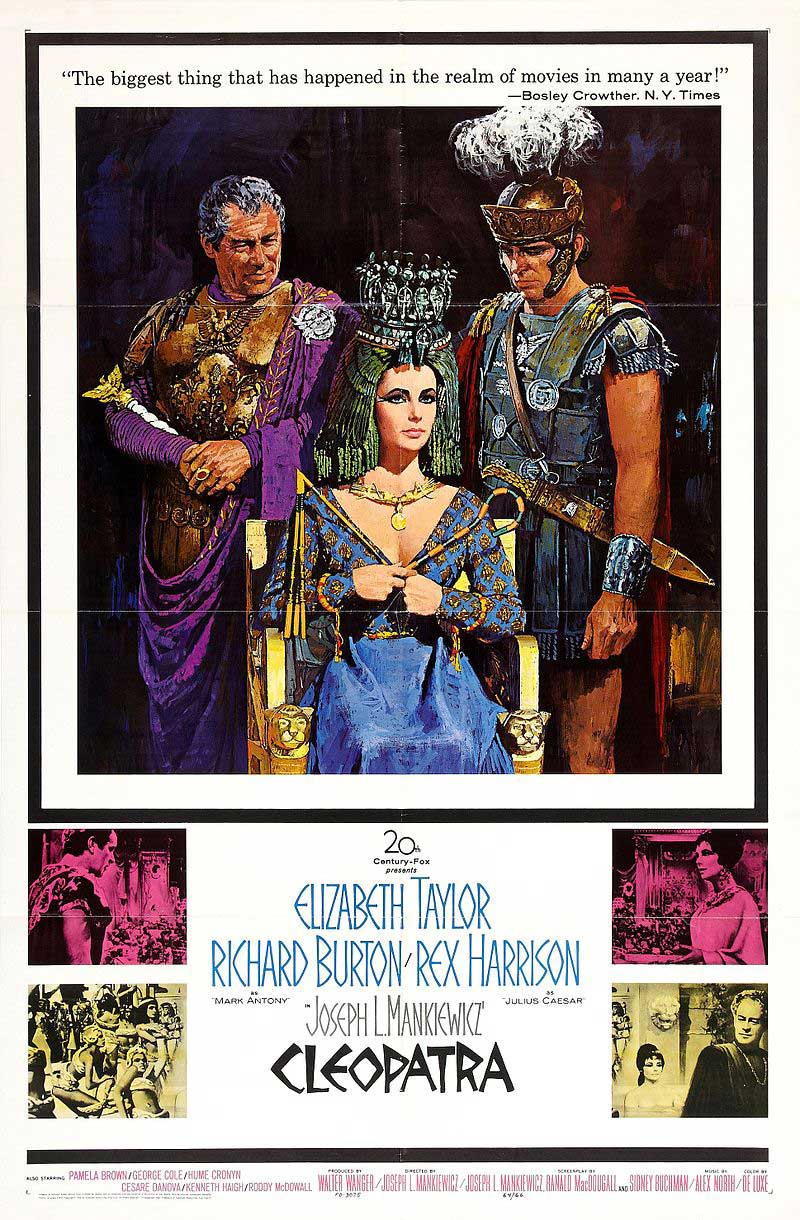

1963 epic “Cleopatra,”

Theatrical poster for the 1963 epic “Cleopatra,” starring Elizabeth Taylor. (Image courtesy of the Internet Movie Database)

Popular Culture

Perhaps no greater single example of Egyptomania in mid-20th century media exists than the film epic “Cleopatra” (1963). Starring the biggest film star of her day, Elizabeth Taylor, in the title role, “Cleopatra” was the most expensive film ever made until that point, with production costs topping $31 million. The film was a true treat for the eyes, with ancient Egypt brought to life in dazzling color.

“Cleopatra,” though, like so many other films, was plagued by scandal, even in the pre-production phase – rumors of an extramarital affair between Taylor and her co-star Richard Burton lived on the lips of the Hollywood elite and were reproduced in gossip magazines of the day. Despite those rumors (or maybe because of them), moviegoers eagerly flocked to theaters to enjoy the grandeur of the ancient world.

Though “Cleopatra” was a box office success, ticket sales were far from enough to cover the production costs, leaving many to believe the film itself to be a flop, despite being one of the highest-grossing films of the entire decade of the 1960s. Not exactly so, says filmmaker Kevin Burns.

“The film was not a bad film. It was not a flop. It was too expensive,” Burns told The L.A. Times in a 2001 article. “It was a financial mess, but it made $24 million in its initial release. It was one of the top 10-grossing films of the ‘60s. It was by no means a failure on any level. It is one of the most beautiful films ever shot. It has some incredible performances. It is very intelligently written and deserves to be seen.”

More than 30 years after the release of that epic, “The Mummy” film trilogy starring Brendan Fraser proved that, even as we faced the dawn of a new century, Egyptomania in media remained alive and well.

Egyptian Revival center table

This Egyptian Revival center table features the likenesses of pharaohs and hieroglyphics – not to mention the marble top. It was likely

manufactured by the Victorian-era Pottier and Stymus Manufacturing Co. of New York. (Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art)

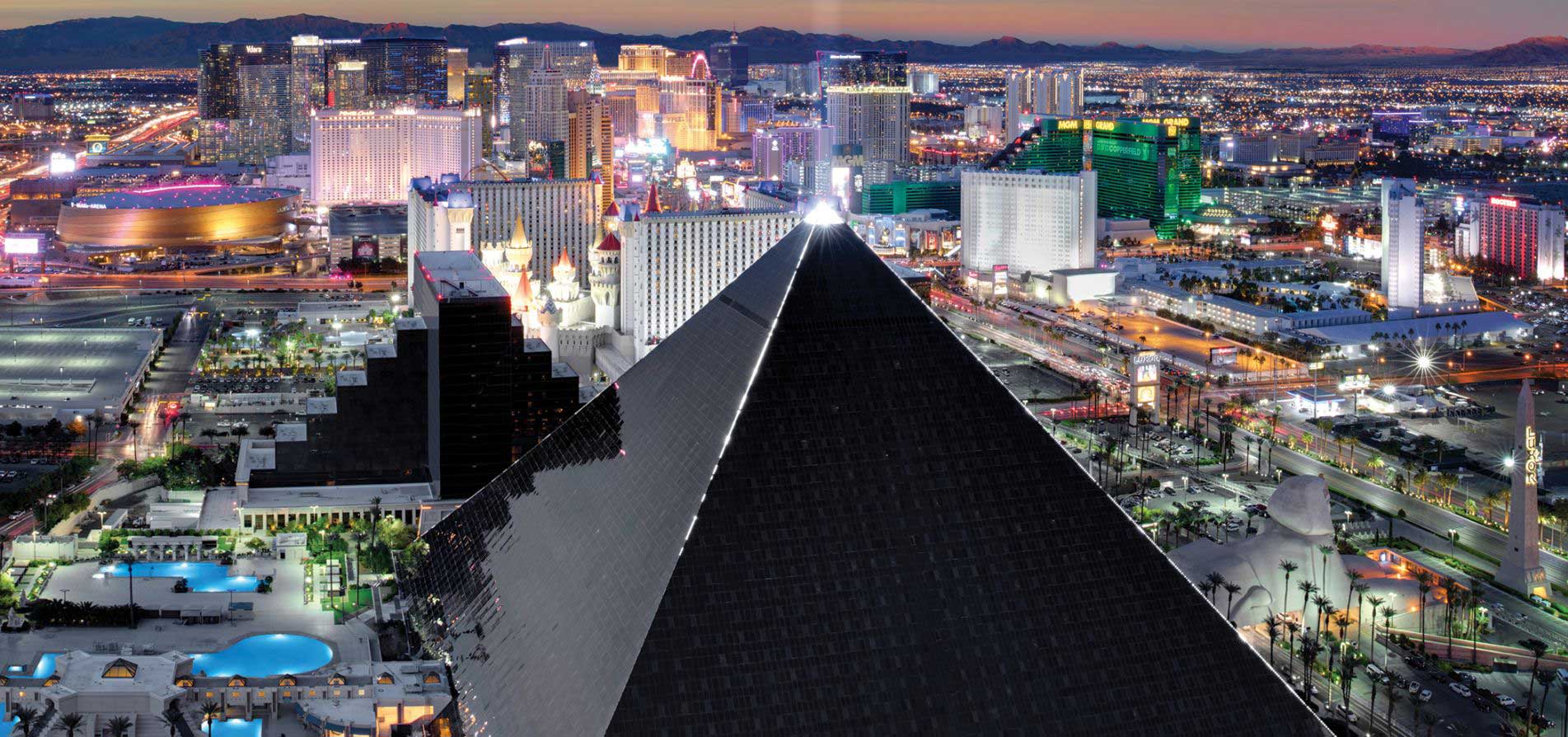

The Luxor

The Luxor’s sky beam, often called the brightest light in the world, is brighter than 42,000 lighthouses combined, according to MGM Resorts. It’s powered by 39 Xenon lights with 7,000-watt bulbs. (Image courtesy of Vegas Means Business)

Architecture and interior design

The Egyptian Revival style of architecture mimicked the motifs and symbols – as well as the grandiose temples and palaces — of the ancient civilization. This was present not only in the buildings of the post-Napoleonic world but in funerary monuments, which made particular use of the obelisk and geometric renderings of palm fronds on grave markers and mausoleums in American cemeteries. Visit any cemetery today and you’ll see such features prominently included.

In the late 19th century, inside the homes of the living, meanwhile, Egyptian Revival-style furniture could be easily found.

“The Egyptian Revival took imagery and art from ancient Egypt and used them in a different light for western tastes,” according to UK-based Nicholas Wells Antiques. “The Egyptian Revival decorative art and architecture inspired artists from all over the world. The people of France, in particular, became very interested in Egyptian Revival decorative art and incorporated everything from lotuses, winged lions, and sphinxes on furniture and architecture. Some of the most famous Egyptian decorative revival furniture included ornamented armchairs with goat feet and pharaoh’s heads, elegant and overstuffed sofas with designs of lotus blossoms, and palmiform columns. These exotic designs added high fashion to the upper-class homes of France.”

Here in the United States, particularly in the Midwest, Egyptian Revival in architecture lives on in establishments such as the Cairo Supper Club in Chicago. Designed in 1920, the one-story building’s exterior “is adorned with glazed polychromatic terra-cotta, lotus-capped columns, and a winged-scarab medallion in the cornice,” according to the Art Institute of Chicago. “The Egyptian-themed façade combined with the Art Deco-inflected neon lights and large plate-glass windows seems to provide a vivid marriage of two different but equally influential cultures.”

In the nation’s capital, the Washington Monument pierces the skyline. Completed in 1884, the structure was “built in the shape of an Egyptian obelisk, evoking the timelessness of ancient civilizations … The Washington Monument embodies the awe, respect, and gratitude the nation felt for its most essential Founding Father,” according to the National Parks Service. “When completed, the Washington Monument was the tallest building in the world at 555 feet, 5-1/8 inches.”

And on the other side of the country, in Las Vegas, stands the Luxor Hotel and Casino, perhaps the most recent example of Egyptomania in architecture. The Luxor opened in 1993, and the pyramid-shaped resort, named after the Egyptian city, features two ziggurat towers; the resort’s pyramid is flanked by an obelisk and a replica of the Great Sphinx of Giza as well. When it originally opened, the hotel included a replica of King Tut’s tomb; that feature has since closed.

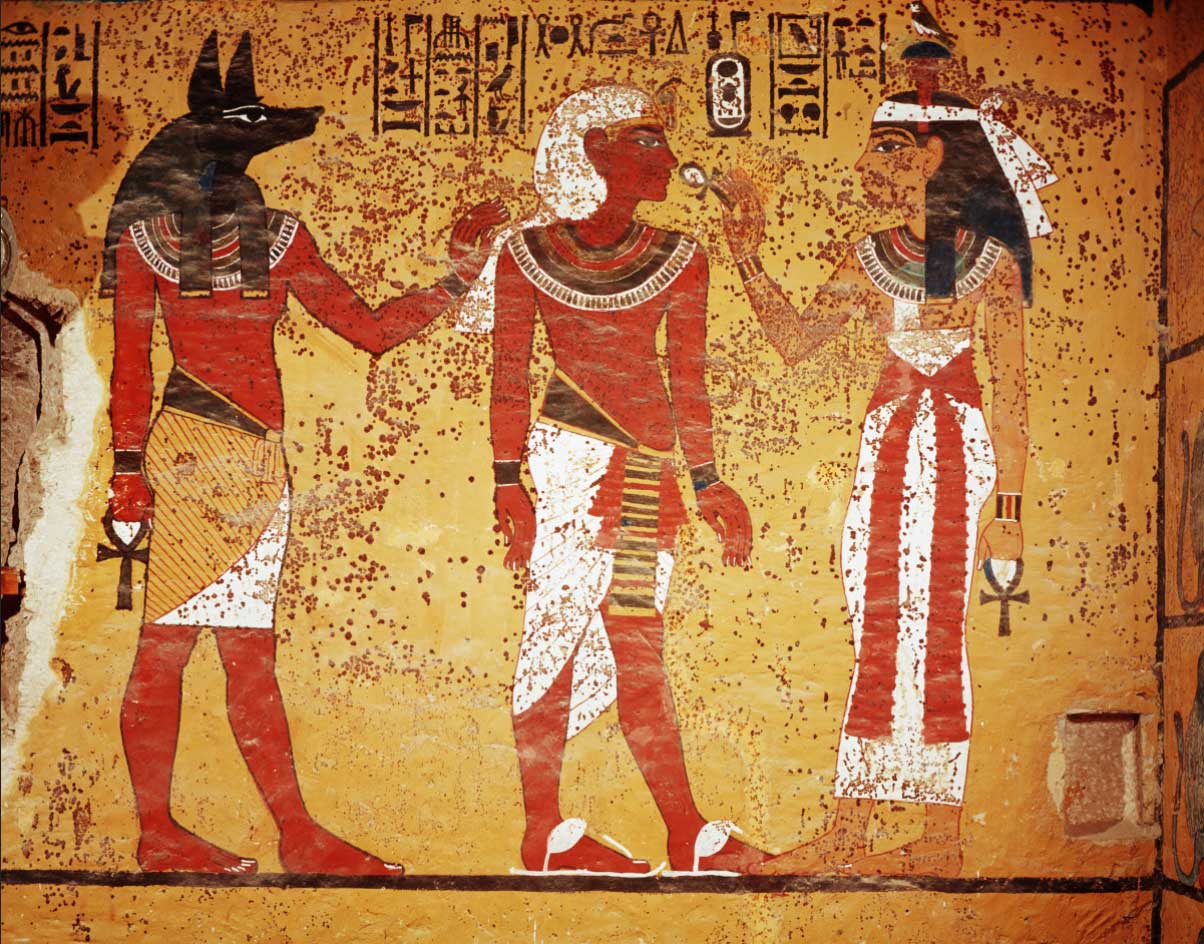

South Wall of the burial chamber of Tutankhamun

A section of the south wall of the burial chamber of Tutankhamun. The images show the fashion of the day, including an animal headdress. (image courtesy of History.com)

Capturing our imagination

Given all of these examples of Egyptomania, ultimately, why does it endure? Scholar Tyler Vuillemot has the simplest theory.

“One of the main reasons is that accounts of life in Ancient Egypt conjure up grand images in our minds: wealthy and powerful kings and queens, enormous breathtaking buildings, endless piles of gold, and mystical gods,” writes Vuillemot of Michigan State University’s Department of Anthropology on MSU’s website. “These things are the essence of all the adventure tales and fantasies that we have heard our entire lives. Romanticized tales of that sort capture our imagination when they are fiction, but the fact that these things actually existed in history adds to the appeal.”

Dazzling collection of Egyptian-inspired jewelry

Late last year, auction house Sotheby’s put a dazzling collection of Egyptian-inspired jewelry on display to mark the 100th anniversary of Howard Carter’s discovery of King Tut’s tomb. (Image courtesy of Forbes)