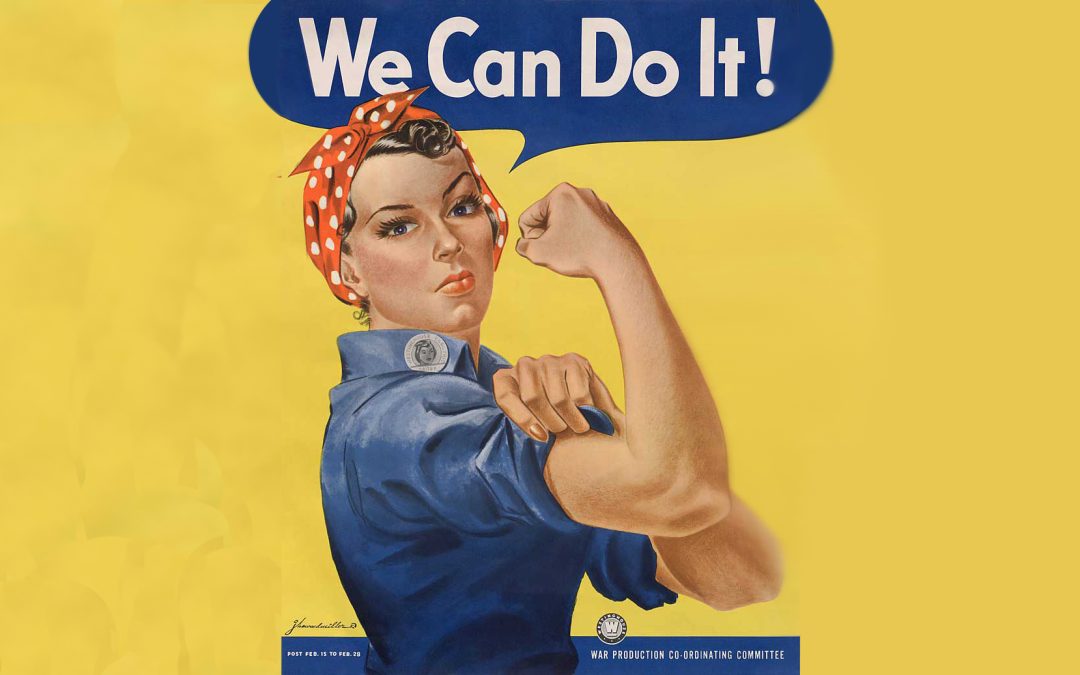

J. Howard Miller’s “We can do it!” poster was designed to boost morale among American women who went to work in factories and in shipyards during the labor shortage created by World War II. (Image courtesy of 1st Dibs)

November 2023

Cover Story

Posters’ Persuasive Power

U.S. propaganda during WW II attempted to rally Americans around war effort

by Corbin Crable

While the Second World War raged across the ocean, a battle for the minds of servicemen and everyday Americans was being fought at home.

The weapons employed in that fight included posters, brochures, and even movies and cartoons. And while they didn’t have the power to take lives, but they did have the power to shift public opinion.

“Persuading the American public became a wartime industry, almost as important as the manufacturing of bullets and planes,” according to an article from the website of The National Archives. “The government launched an aggressive propaganda campaign with clearly articulated goals and strategies to galvanize public support.”

Uncle Sam needs you

Combinations of dominant, strong, physically imposing figures and imagery along with calls to action comprised portrayals of American superiority and the need for civilians to do whatever they could at home to support their boys overseas. Meanwhile, American depictions of the Axis Powers – Germany, Italy, and Japan – painted America’s wartime enemies as sneaky, deceptive, evil racial and ethnic stereotypes in an attempt to instill anger and revulsion in American citizens.

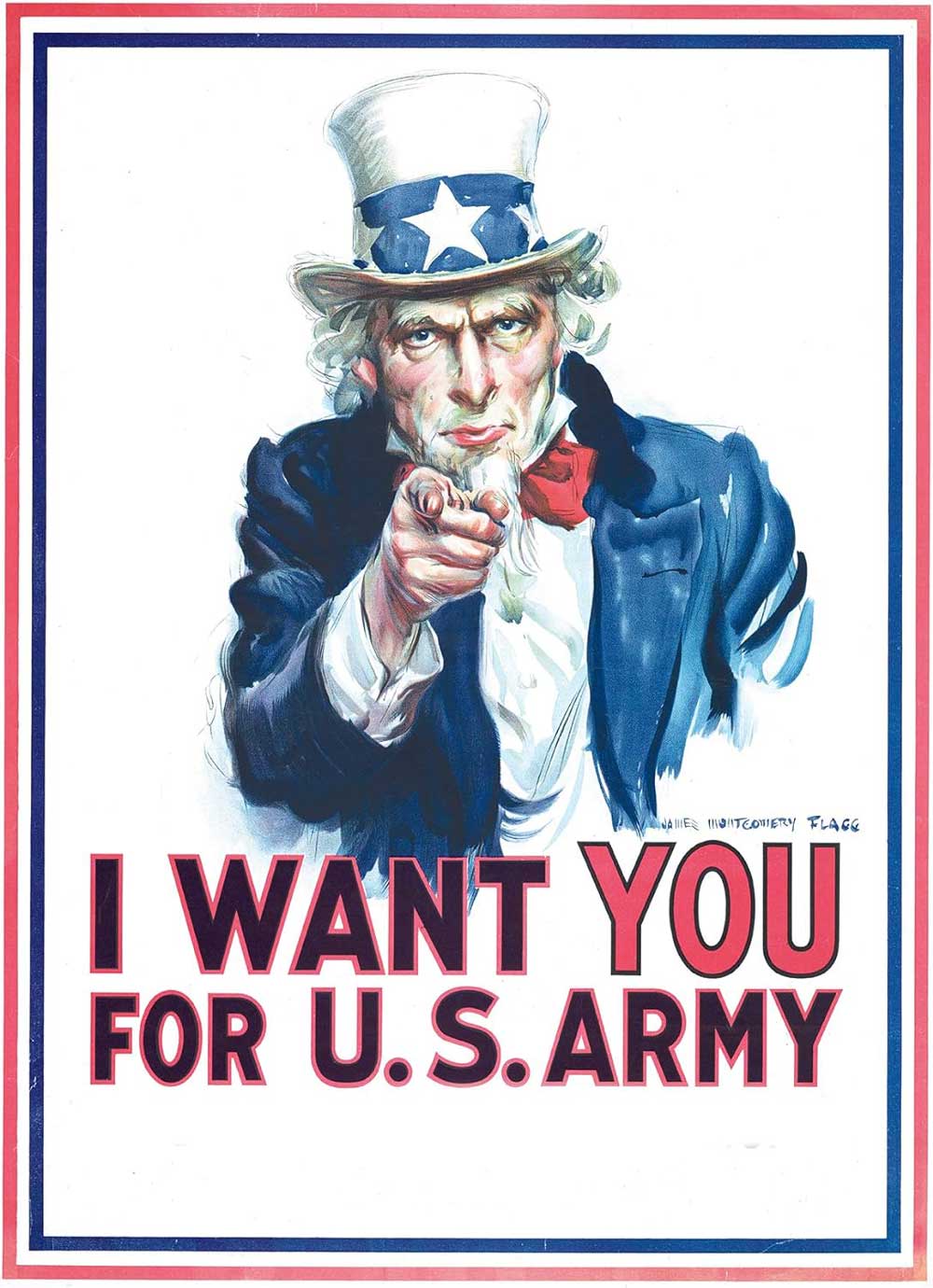

“I WANT YOU” poster in 1917

James Montgomery Flagg created the famous “I want YOU” poster in 1917, the year that America entered World War I. (Image courtesy of the U.S. Army)

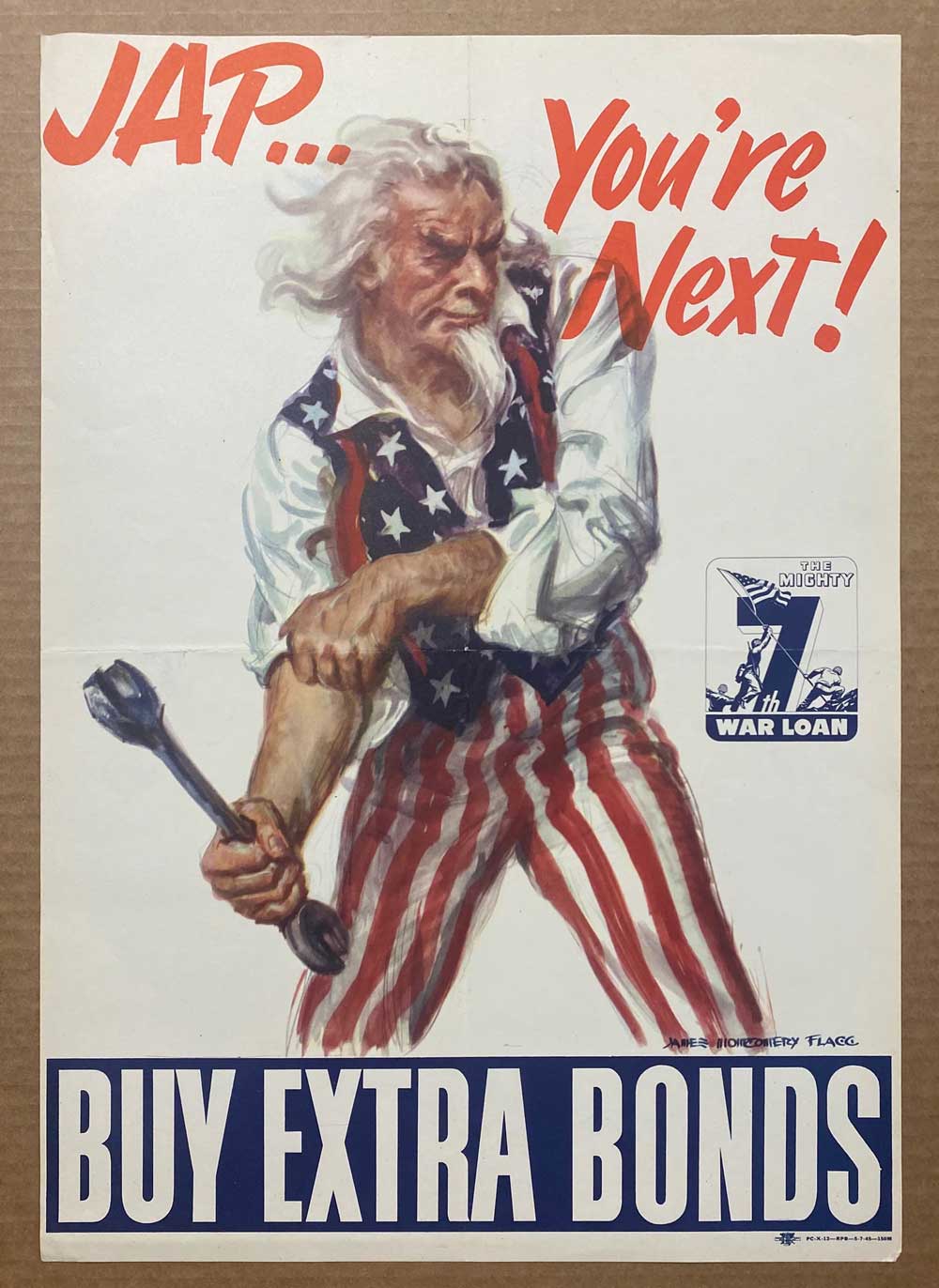

One of the most famous propaganda images wasn’t created during World War II, however. In propaganda posters, American might is most famously personified as Uncle Sam in the now-famous “I Want YOU to enlist for the U.S. Army Now” poster. In that image, created during the First World War by American artist James Montgomery Flagg, Uncle Sam is a white-haired man decked out in traditional red, white, and blue, but his message is direct, his eyes staring directly at the viewer to convey the serious and urgent nature of his plea. In another poster, Uncle Sam has shed his star-spangled top hat, his white hair wild and flowing as he rolls up his sleeves and wields a large monkey wrench as he threatens the “Jap” and urges his audience to buy war bonds, used to by the government to finance war operations without raising taxes too high.

“Masculine strength was a common visual theme in patriotic posters,” the National Archives article reads. “Pictures of powerful men and mighty machines illustrated America’s ability to channel its formidable strength into the war effort. American muscle was presented in a proud display of national confidence.”

Put down that sugar bowl

Besides calling on Americans to buy war bonds, American propaganda posters issued other calls to action that allowed civilians to help their servicemen – or at least to create the appearance of helping. Rationing of items such as sugar, butter, meat, gasoline, and even rubber was commonplace, fueled by the posters issued by the federal government. These items were badly needed by the troops, it was argued, and the American civilian’s willingness to ration them displayed patriotism and support of the military that fought for them overseas. Sugar was the first item rationed, and families across the country lined up at schools and other community gathering places to receive ration books that employed a point system, which allowed each family a certain amount of processed goods and a certain amount of perishable goods each month. These ration books can still be found in antique stores everywhere. Though propaganda posters attempted to drum up support for rationing, it was seen as a sacrifice Americans had to make if they wanted the defeat of the Nazis, who continued to march across Western Europe and conquer its countries in their wake.

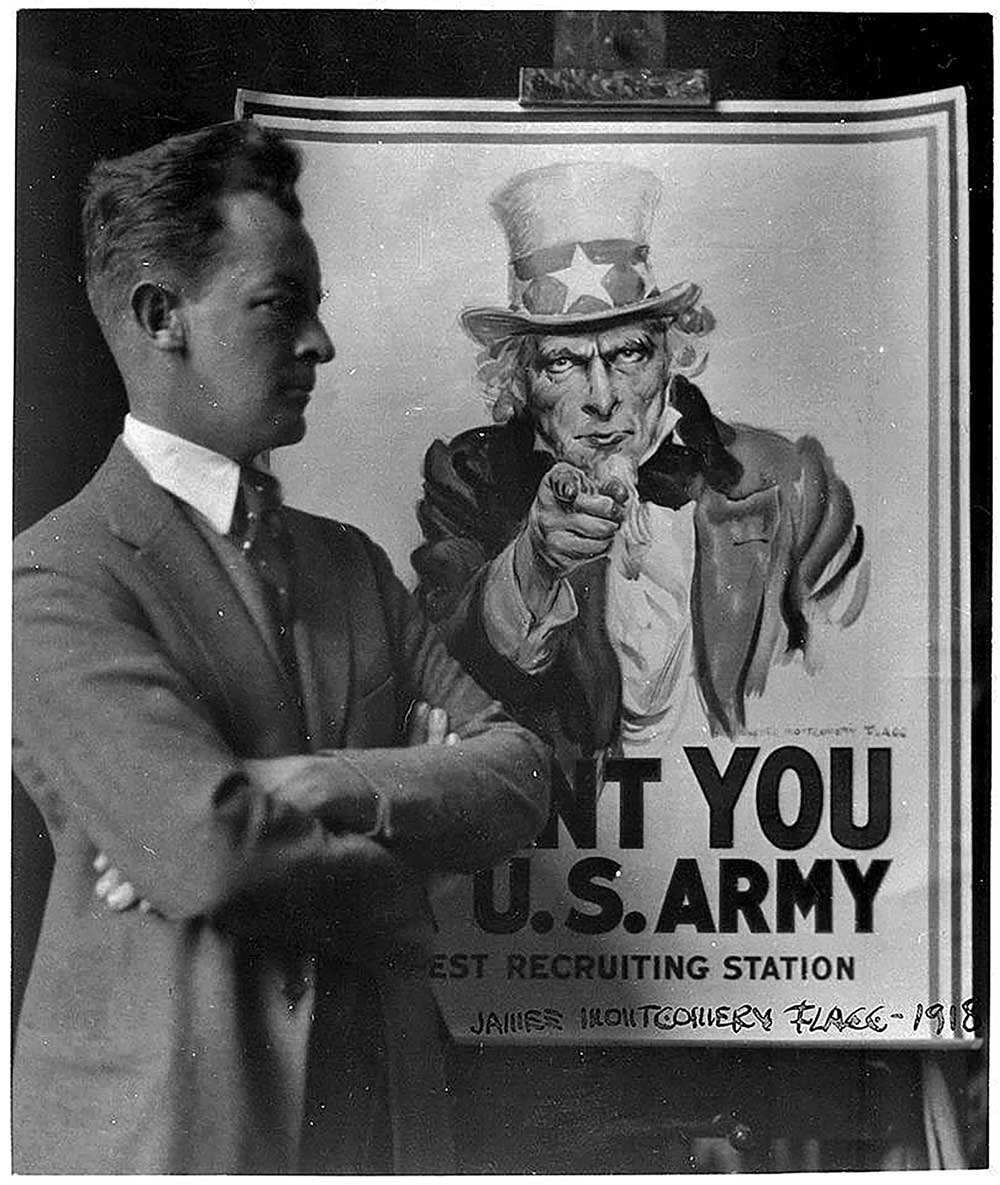

Artist James Montgomery Flagg

Artist James Montgomery Flagg poses beside his poster to encourage recruitment in the U.S. Army during World War I. (Image courtesy of the U.S. Army)

Norman Rockwell’s “Freedom From Want”

Artist Norman Rockwell’s “Freedom From Want” is one in a series of four oil paintings inspired by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1941 State of the Union address. The four paintings ran in The Saturday Evening Post; they were eventually distributed as posters and used in the government’s drive for war bonds. (Image courtesy of The Norman Rockwell Museum)

Buy Extra Bonds

Flagg returned to his drafting desk to create this poster in 1945. (Image courtesy of The Ross Art Group)

“Food was in short supply for a variety of reasons: much of the processed and canned foods were reserved for shipping overseas to our military and our Allies; transportation of fresh foods was limited due to gasoline and tire rationing and the priority of transporting soldiers and war supplies instead of food; imported foods, like coffee and sugar, was limited due to restrictions on importing,” according to the website of the National World War II Museum in New Orleans. “Because of these shortages, the U.S. government’s Office of Price Administration established a system of rationing that would more fairly distribute foods that were in short supply. Every American was issued a series of ration books during the war. The ration books contained removable stamps good for certain rationed items, like sugar, meat, cooking oil, and canned goods. A person could not buy a rationed item without also giving the grocer the right ration stamp. Once a person’s ration stamps were used up for a month, she couldn’t buy any more of that type of food. This meant planning meals carefully, being creative with menus, and not wasting food.”

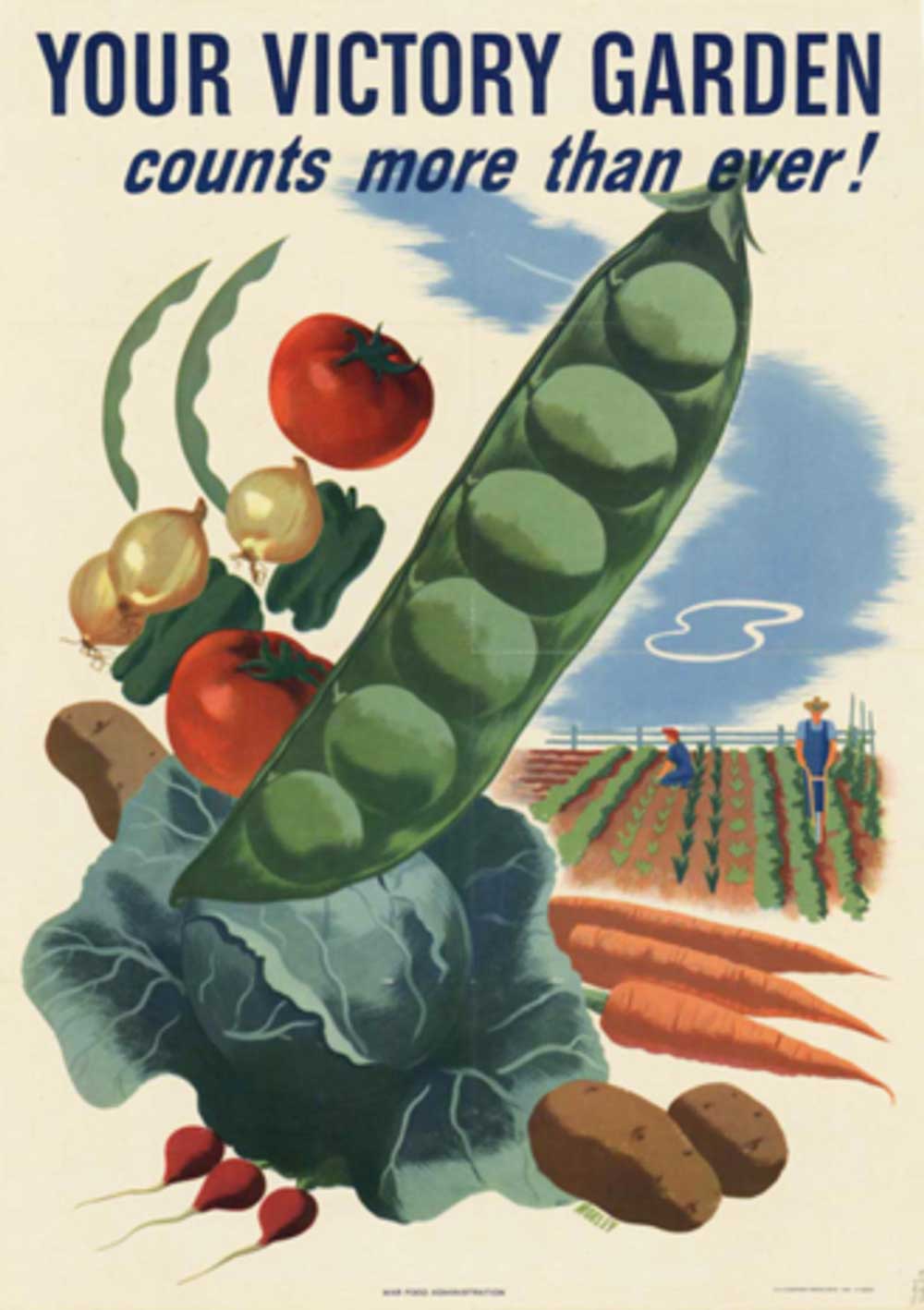

A Victory Garden

A Victory Garden was one way everyday Americans could help soldiers win the fight overseas. Poster produced in 1943 by artist Hubert Morley. (Image courtesy of CBS News)

Vegetables for victory

Propaganda posters instead encouraged Americans to grow their own war gardens, rebranded as “victory gardens.” The purpose of this program, devised by the federal government, was to “free up agricultural produce, packaging, and transportation resources for the war effort, and help offset shortages of agricultural workers,” according to the website of The National Park System. Communal gardening was especially encouraged – everywhere from public land to vacant lots to city rooftops.

Propaganda posters also touted a solution to the labor shortage caused by the war – employing women in the nation’s factories to produce ammunition and war supplies to be used in the war effort. From this shift of women from the home to the workplace came the now-famous image “We Can Do It!” poster of a young female worker, made by artist J. Howard Miller and designed to boost morale among the nation’s female workers. The poster and “Rosie the Riveter” image – though it was never referred to as such during the war – became icons synonymous with the feminist movement in the later half of the 20th century.

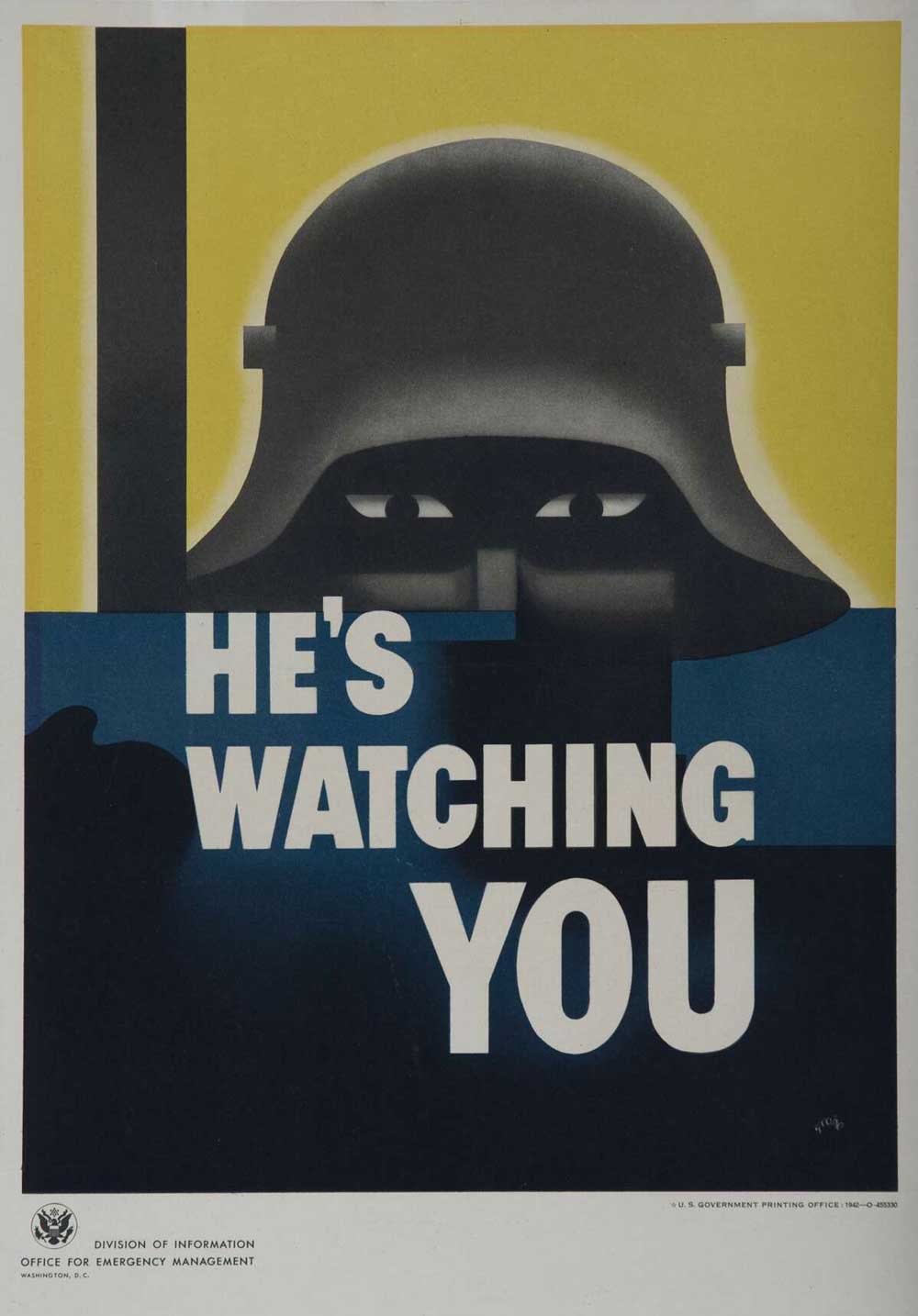

In addition to encouraging the elimination of waste in most facets of daily life, making sacrifices for the greater good, and expressing the power of American military forces, propaganda posters during World War II also served to caution their audience. They instilled fear in Americans by portraying the enemy, the acts of atrocity committed by the Axis powers, and their overall sinister nature. They convinced us that danger was lurking around every corner, and that complacency equaled peril.

“Public relations specialists advised the U.S. government that the most effective war posters were the ones that appealed to the emotions,” The National Archives article explains.

Beware of the enemy

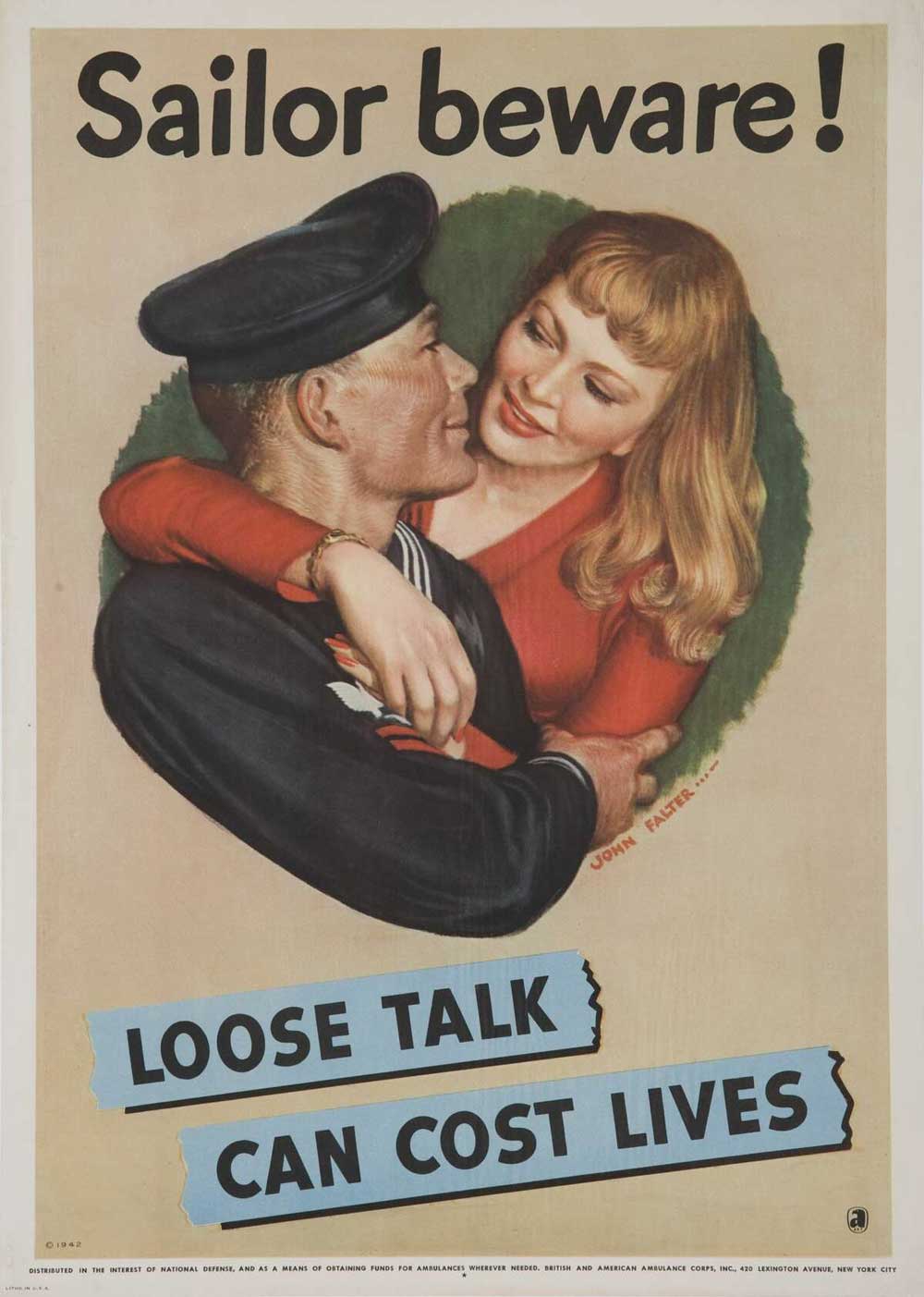

Posters also warned Americans to always be aware of their surroundings and warned them against sharing any sensitive information. After all, you never know when a spy is listening.

“Concerns about national security intensify in wartime. During World War II, the government alerted citizens to the presence of enemy spies and saboteurs lurking just below the surface of American society,” according to The National Archives. ’Careless talk’ posters warned people that small snippets of information regarding troop movements or other logistical details would be useful to the enemy. Well-meaning citizens could easily compromise national security and soldiers’ safety with careless talk.”

Those posters that didn’t make us feel proud of our country and exploit that patriotism by encouraging sacrifice were instead presenting caution – that the atrocities occurring in another land could just as easily happen on our shores, so always beware.

Mr. Capra goes to Washington

Posters, of course, weren’t the only medium through which propaganda spread during the war. The medium of film was a powerful tool that expressed many of the same sentiments to the public in newsreels shown in movie theaters before the main feature began.

The U.S. Department of War commissioned filmmaker Frank Capra to produce the series of seven propaganda films written to help American soldiers understand why the U.S. was involved in the war. The series, titled “Why We Fight,” was produced between 1942 and 1945.

Sailors were reminded that careless words

In this poster, “sailors were reminded that careless words shouldn’t be spoken to their female dates, who could be spies.” (Image courtesy of Chron.com)

Posters promoted car-sharing

Posters promoted car-sharing clubs, which saved gas and rubber needed for the war effort. This poster was designed in 1943. (Image courtesy of Yale University)

While Hitler and the Nazis had their own propaganda filmmaker in Leni Riefenstahl, Capra was an Academy Award-winning filmmaker whose career had soared in the 1930s with films like “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington.” Capra, who would go on to direct the Christmas classic “It’s a Wonderful Life,” even teamed up with Walt Disney Productions for the series, with Disney producing the several animated segments in the films. Capra later said he intended for “Why We Fight” to stand as the American response to Riefenstahl’s nightmarish “Triumph of the Will,” a documentary that covers the Nazi Party’s 1934 rally in Nuremberg. An article in The Western Journal of Speech and Communication from author Kathleen German stated that the medium of film accomplished what printed material like posters and other literature could not – that it employed the viewer’s senses of sight and hearing, bringing the battle between good and evil to life for audiences living in a world that was receiving more and more of its information from visual sources with each passing year.

Though World War II ended in 1945, the military continues to produce posters, “not just to attract recruits, but also to send messages to troops, such as instilling values, promoting safety and preventing sexual assault,” according to the U.S. Department of Defense.

A sinister-looking German soldier

A sinister-looking German soldier peers at the viewer. Such images were meant to instill fear in American civilians. (Image courtesy of Chron.com)